Even before 'What Happens Here,' Vegas always understood how to market itself

What happens here, stays here, except when it’s in a TV commercial, or on social media, or the subject of a film.

That slogan has become legendary and ubiquitous since it began two decades ago as part of a “Vegas Stories” advertising campaign.

Few remember “Vegas Stories,” or much of the marketing of Las Vegas that came before, but the area has a long, rich and often successful history of knowing how to sell the product, which is itself.

As the Clark and McWilliams townsites grew after the May 1905 auction of railroad land Downtown, the Las Vegas Board of Trade began promoting the area. The Las Vegas Promotion Society followed, and then, in 1911, the Chamber of Commerce. It produced pamphlets calling Las Vegas the “city of destiny.”

These groups advertised everything from its desert climate—ideal for those escaping eastern cold for fun or for their health—to how Las Vegas was sure to imitate other parts of Nevada in becoming a major mining or agricultural boomtown.

By the late 1920s, Las Vegas leaders had realized that tourism was crucial to their future. Air service and federal and state highway building made it easier to reach Las Vegas and its county fairgrounds and rollicking Block 16. Just as Reno announced itself on Virginia Street as “The Biggest Little City in the World,” a Fremont Street sign proclaimed Las Vegas as “The Gateway to Boulder Dam” (then to Hoover Dam), which became a tourist attraction, drawing hundreds of thousands to gape at its construction.

As Las Vegans worried about their future after the thousands of dam workers departed, they turned to a past that never was. The annual Helldorado became a major regional event, with a rodeo, parade and various Western-style hijinks.

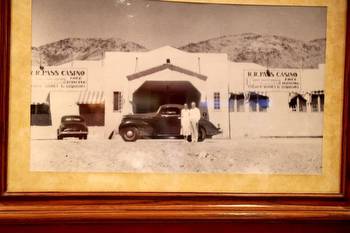

After the state legalized gambling in 1931, the first themed casinos appeared, with sawdust floors, some of the employees in Western garb and names like the Frontier Club, Boulder Club, Apache Hotel and Northern Club underscoring Las Vegas’ marketing of itself as “Still a Frontier Town.”

Except for Southern Paiutes, however, the 19th-century population never exceeded three dozen.

The first hotels on the Strip continued the theme. The El Rancho Vegas’ name suggested the Old West, and its Chuck Wagon Buffet drove home the point. The Hotel Last Frontier featured barstools that evoked saddles, steerhorns on the beds, and a Western theme park, Last Frontier Village. Its ads referred to “The Old West in Modern Splendor.”

Las Vegans also knew how to take advantage of celebrity. When Ria Gable came to town to establish a six-week residency to divorce her husband, Clark Gable, Chamber of Commerce president Robert Kaltenborn persuaded his colleagues to spend $500 marketing her presence.

Showing that a Hollywood celebrity, or the soon-to-be ex-wife of one, could enjoy Las Vegas convinced lesser-known Americans that they might have fun and see stars here.

Entertainment was crucial to the next phase of marketing Las Vegas. While the Flamingo began the trend toward mob ownership and luxury properties, its showrooms also provided big-name performers, such as Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis, Jr., along with a glittery pianist, Liberace.

They became part of the marketing as the Chamber hired outside advertising agencies, then brought the work in-house with the Las Vegas News Bureau. Photographers and hotel publicists conspired on photos and videos they sent around the country, emphasizing that Las Vegas was, as one video put it, “the land of daytime sun and nighttime fun.”

The fun included seeing Sinatra ride an elephant, as he did to promote the Dunes Hotel, and Sands publicist Al Freeman creating a real floating craps game to mirror the one in Guys and Dolls.

In the decades that followed, Las Vegas went through numerous slogans and campaigns.

In the 1990s, marketing to families became the approach. The Baby Boom generation now had children, and those kids needed something to do when their parents traveled.

Theme parks, rides and arcades dotted the Strip. When that advertising effort ran its course, some of the attractions stayed (such as the Mirage’s white tigers, and of course the amusements at Circus Circus), but others gave way to bigger moneymakers, such as the MGM Grand replacing its theme park with a conference center.

By the early 2000s, Las Vegas wanted to let potential visitors know that while families might be welcome, they could still find the sin in Sin City. Assuring them that what happened here would stay here meant they could be bad in relative obscurity—unless they wound up on social media, as Prince Harry did at one point after a game of strip billiards.

Nearly two decades after that award-winning campaign began, Las Vegas keeps returning to it or versions of it, just as it keeps advertising its entertainment—now big concert venues, professional sports and celebrity chefs instead of the Rat Pack.

Whatever the future holds, Las Vegas will try to adapt to it, and make sure that what is happening here doesn’t just stay here.