Chicago casino too risky for some industry players

Casino operators, accustomed to having an edge, are having trouble finding one in Chicago’s request for proposals to build a first-class gambling complex that would prop up its police and fire pension funds.

Four large gambling companies expressed an interest in Chicago’s plans late last year. But two have since folded their hands. A third interested party, Chicago’s Rush Street Gaming, owner of the Rivers Casino in Des Plaines, said through a spokesman it is still deciding how to respond to the “unique opportunity.”

Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s administration could hear from other bidders, including real estate developers. But industry experts say Chicago’s ambitious call for perhaps a $1 billion investment—including a 500-room 5-star hotel and an entertainment venue—is drawing skeptical analyses. Some contend there’s little potential here to expand traditional gaming and that the risk is too great to meet the city’s aspirations for something close to a resort.

“The casinos in the state have been in nothing but a downward spiral for a decade, except for Rivers,” said Alan Woinski, president of Gaming USA, a consulting firm and newsletter publisher. “There’s no reason to believe that if you add a casino downtown that you’ll do anything but cannibalize the others, including Rivers. It’s kind of a zero-sum game and everybody loses.”

City officials did not answer requests for comment Monday.

Critics also see obstacles such as a tax rate many view as prohibitive. A recent proposal to bring sports betting to Chicago stadiums also could amount to competition that scares off a mega-casino.

Woinski said sportsbooks aren’t big moneymakers for casinos, but they draw crowds. If the action happens elsewhere, “that’s one less reason for people to physically go to the casino,” he said.

Other cities, Woinski said, have had mixed results with casinos, especially if there are other entertainment options.

City Hall has set an Aug. 23 deadline for responses to its casino call. The responses are supposed to include proposed sites. Lightfoot has declined to express a site preference, but the parameters the city set out would point to something downtown, convenient to locals and visitors. The city wants a site that maximizes tax revenue, which it has earmarked for pensions.

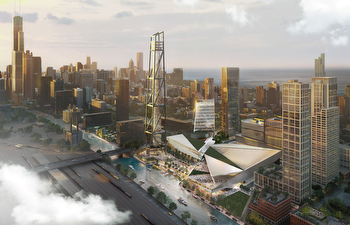

Another “core goal” respondents must meet is offering a development “of superb quality and architecturally significant design,” according to the city’s request for proposals published in April.

It’s all too much for Bill Hornbuckle, CEO of MGM Resorts International. After the city issued its full request, Hornbuckle told stock analysts that “Chicago is just complicated. The history there in Chicago, the tax and the notion of integrated resort at scale don’t necessarily marry up. And while I think they’ve had some improvement, we’re not overly keen or focused at this point in time there.”

MGM voiced interest in a Chicago site last year when it responded to a city survey about casino issues. A spokeswoman for Wynn Resorts, another firm initially interested in Chicago, said it has “decided not to participate in the request for proposals.”

The remaining gaming giant that expressed interest a year ago, Hard Rock International, could not be reached.

Some analysts believe Rush Street will propose a casino for the development site downtown known as The 78. It covers 62 vacant acres southwest of Roosevelt Road and Clark Street. Rush Street has formed a partnership with Related Midwest, the developer of The 78.

The property provides ample room for a casino and ancillary uses the city wants, and development could occur in phases. But any casino site could provoke opposition over traffic and other zoning concerns.

A downtown casino would face a 40% tax rate, said a report Union Gaming Analytics prepared for state officials. The state legislature cut that amount from 72% in a prior casino law after Union Gaming found the tax load too onerous.

City officials contend there is room here to “grow the pie,” or increase the size of the gaming market. In 2019, Union Gaming found that per-capita spending on gaming in the Chicago area was half that of other metropolitan regions.