Chicago’s Casino Won’t Be Built at McCormick Place, Officials Announce As 3 Finalists Unveiled

Officials have whittled down the five proposals submitted by three firms to build a casino and resort in Chicago to eliminate both proposals that would have built the gambling palace at McCormick Place, city leaders announced Tuesday.

That leaves all three firms that bid for the long-awaited Chicago casino still in the running to build and operate the facility. Mayor Lori Lightfoot and the Chicago City Council are counting on a casino to boost the city’s economy and funnel approximately $200 million into the police and fire pension funds, significantly easing the pressure on the city’s finances, while creating thousands of jobs and drawing tourists — and their fat wallets.

The finalists are:

- The $1.62 billion proposal from Rush Street Gaming, led by Chicago billionaire and Rivers Casino Des Plaines operator Neil Bluhm. Plans call for a casino and resort to be built on vacant land between the South Loop and Chinatown along the Chicago River on land set to be redeveloped by Related Midwest into a new development known as The 78.

- The $1.74 billion proposal from Bally’s to build the casino and resort on what is now the Chicago Tribune printing plant and newsroom near Chicago Avenue and Halsted Street.

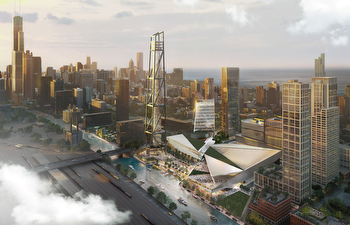

- The $1.74 billion proposal from Hard Rock to build the casino and resort as part of the proposed One Central development, across from DuSable Lake Shore Drive from Soldier Field.

Lightfoot does not expect to pick one of the three finalists and ask the Chicago City Council to ratify her decision until early summer, a significant delay since the fall, when the mayor’s office unveiled the five bids for the Chicago casino. In December, Lightfoot said she expected to make a decision in early 2022.

Chief Financial Officer Jennie Huang Bennett said the decision to narrow down the casino proposals would allow the city to conduct an “authentic” community engagement process to allow Chicagoans to review the details of the proposals and weigh in at three sessions set for April 5, April 6 and April 7.

At the same time, Huang Bennett acknowledged that every month that passes without a casino up and running costs the city millions of dollars.

“Time is of the essence for us,” Huang Bennett said.

Samir Mayekar, deputy mayor for economic and neighborhood development, said that process is designed to make sure Chicago’s casino is an “iconic” addition to the city’s world-class architectural history and puts Chicago on the “global map” for gamblers.

In addition to the approval of the Chicago City Council, the casino proposal also needs the endorsement of the Illinois Gaming Board.

Bally’s proposal to build a casino on what is now the home of the Chicago Tribune would be the most lucrative for the city and its sister agencies, according to a report released Tuesday by the mayor’s office from Union Gaming, the city’s gaming consultant.

A Bally’s casino with 3,400 slots and 173 table games as well as a 500-room hotel west of River North would generate $191.7 million in its sixth year of operations, according to the study.

The Rush Street casino at the 78, which includes 2,600 slots and 190 table games, would generate $174 million for the city and its sister agencies, the least amount of the three remaining casino proposals, according to the study.

However, that estimate relies on the construction of a planned observation tower and hotel as part of the resort, and Rush Street officials have not yet provided city officials with evidence they will be able to obtain financing for that part of their proposal. Rush Street officials said they planned to provide those assurances to city officials.

All three firms told city officials they will meet the requirements imposed by city officials that 25% of the facility be owned by Black, Latino or Asian shareholders, 50% of its employees be from Chicago and at least 26% of the construction contracts go to firms owned by women or Black, Latino or Asian Chicagoans.