Why did Camelot lose the UK national lottery licence?

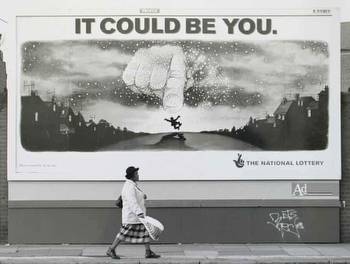

When the national lottery was launched in 1994, via a TV spectacular watched by more than a third of the population, the famous advertising slogan promised: “It could be you.”

It won’t be Camelot though, at least not from 2024.

During its tenure of nearly three decades as the lottery’s operator, Camelot outlasted five prime ministers, fought off challenges from the likes of Sir Richard Branson and navigated the rise of the internet and the smartphone.

Now, barring a successful judicial review by Canadian-owned Camelot, which now has a 10-day “cooling-off” period to consider its next move, the torch will be passed on.

The fourth ever battle for the lucrative licence ended in defeat to Czech-owned Allwyn, which also fended off competition from media tycoon Richard Desmond and Sisal, an Italian firm whose bid was complicated when it was bought for £1.6bn, midway through the competition, by Paddy Power owner Flutter.

The big question is what Allwyn’s victory means for consumers, for the good causes that the lottery funds, for Camelot and its 1,000 staff in Watford, and for the new stewards of a game played by nearly 10 million people in the UK.

Ultimately owned by the Czech billionaire Karel Komárek, Allwyn already runs lotteries in the Czech Republic, Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Austria.

To boost its efforts to add the UK to the stable, Allwyn hired an all-star cast of business luminaries. Leading the charge was Sir Keith Mills, whose Midas touch moments include inventing the Air Miles and Nectar Points loyalty schemes, as well as running London’s successful bid to host the 2012 Olympics. He was joined by former Sainsbury’s boss Justin King, who chairs Allwyn UK and worked with Mills on the delivery of the games.

For the time being, the Gambling Commission won’t say what magic dust this duo were able to sprinkle to unseat Camelot. The competition process is shrouded in secrecy, so much so that a scorecard process during which the rivals were marked on categories such as technology and planned returns to good causes, used code names rather than the companies’ real ones. One well-placed source said that only two people knew which codenames applied to which bidder.

While the regulator is remaining tight-lipped, the Guardian understands that Allwyn’s pitch outshone Camelot’s in two key areas: returns to good causes and efforts to curb gambling addiction.

Camelot has come under pressure several times in recent years, after profits rose faster than returns to good causes, prompting a rebuke from the National Audit Office in 2017.

The company stresses that its profits – about £95m in each of the past two years – amount to 1% of ticket sales. It also points to a recent uptick in good cause money, which fell below £1.5bn in the year of the NAO’s rebuke but has been above £1.7bn in each of the past two years, on the back of record ticket sales of £8bn.

Its 28-year tenure, Camelot says, has led to the return of £45bn to 660,000 causes in the UK.

But Allwyn is understood to have promised to do better than that, pledging money to good causes of more than £30bn over the course of its first 10-year licence.

It aims to do this by recapturing the long lost glitz of the old weekly draw, offering more super-national lotteries, in the vein of EuroMillions, where larger jackpots pull in more players. On top of that, it promises a flood of new technology that it hopes can win a back younger audience which has drifted away from thelottery towards online betting and casino games, leading to a £9m decline in regular players since 1994.

Its technology offering, via a partnership with Vodafone, will also work in shops, so that people can use their phone to access products such as scratchcards, allowing the high street to share the spoils rather than losing sales to the internet.

The licence decision also comes with social responsibility high on the agenda, as the government, spurred by concern about gambling addiction finalises its white paper on regulation.

Camelot has come under fire for seeking to ape the casinos rather than beat them, increasingly relying on more high-octane online Instant Win games. Allwyn is thought to have put responsible gambling at the forefront of its tech-heavy pitch, particularly a plan to impose strict controls preventing people from spending unaffordable sums, such as by playing repeatedly late at night.

If the historic handover from Camelot does go ahead, it would likely be an existential matter for the incumbent. Its owner, the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, is a vast investment fund with nearly £140bn of assets under management. Camelot has been a steady and lucrative investment but its sole raison d’être is to run the UK national lottery.

Without that, it is unclear what Camelot is for. Its chair, Sir Nigel Railton, said on Tuesday that he was “incredibly disappointed” by the decision, while the company declared it was considering its options, potentially including a legal challenge.

Labour said on Tuesday that the government must satisfy itself that Komarek did not have links to Russia. This seems unlikely to be a problem. Komarek has a gas storage venture with Gazprom in his native Czech Republic but has condemned Putin’s “barbarism” and is working with the Prague government on a plan that would see the asset nationalised.

If Camelot can’t overturn the decision , there is at least hope for the 1,000 people who work for it, mostly in Watford. They, the Guardian understands, are likely to be transferred across to the new incumbent.