Supreme Court Sides with Ysleta Tribe in Bingo Case

In an unusual lineup, the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States ruled 5-4 against the State of Texas on Wednesday, thereby blocking the Lone Star State from enforcing its gaming laws against a tribal casino.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the 20-page majority opinion which was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Amy Coney Barrett. The Court’s opinion cleared the way for the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo tribe (along with the Alabama-Coushatta tribe) to operate its bingo-themed casino on the small Ysleta del Sur Pueblo reservation near El Paso.

The dispute between the Ysleta and Texas was over live bingo games and casino-style slot machines. Texas disallowed those games, but the Ysleta argued—and SCOTUS agreed—that the state law at hand does not apply to the Ysleta casino.

The question of whether Texas state gaming laws apply to tribal casinos is a complex one lacking simple analysis. Rather, only some state gaming laws to tribal activities.

Texas argued that the Pueblo are subject to the 1987 Ysleta del Sur Pueblo and Alabama-Coushatta Indian Tribes of Texas Restoration Act (“Restoration Act”), which bars any gaming that violates Texas law. SCOTUS, however, sided with the tribes, and found that the more permissive 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (“IGRA”) controls.

Justice Neil Gorsuch began with a blunt statement about the size of Texas’ authority on the issue of gaming. Gorsuch and the majority said, “we find no evidence Congress endowed state law with anything like the power Texas claims.”

To provide context, Gorsuch recounted some lamentable history.

“Over the years that followed [Texas’ statehood], the Tribe repeatedly lost lands ‘without recompense,'” the justice wrote. What followed, Gorsuch explained, were many years of legal disputes between the Ysleta and Texas. One such dispute resulted in a 1953 Congressional statute that allowed “a handful of States to enforce some of their criminal—but not certain of their civil—laws on particular tribal lands.” Later, a Supreme Court case “left certain States unable to apply their gaming regulations on Indian reservations,” which resulted in fear that SCOTUS had “opened the door to a significant amount of new and unregulated gaming on tribal lands.”

Gorsuch framed the legal issue as one that we’ve seen arise many times outside the context of tribal sovereignty: the distinction between prohibition and regulation. Gorsuch wrote that under past SCOTUS precedent, state laws that “merely regulate a game’s availability” (as contrasted with laws that entirely prohibit a game) are not enforceable on native lands.

“Electronic bingo” games have patrons sit at slot-style machines. However, Gorsuch pointed out, “the underlying game is run using historical bingo draws.” As a result, Texas shut down the games as a prohibition against bingo. Problematically though, Texas’ state laws do not forbid bingo generally. Rather, bingo is allowed subject to fixed rules about time, place, and manner. The majority reasoned “it would seem to follow that Texas’s laws fall on the regulatory rather than prohibitory side of the line,” which therefore means that the Ysleta are not bound to comply.

Gorsuch was clear to point out the scope of the Supreme Court’s authority on the matter at hand, and wrote:

It is not our place to question whether Congress adopted the wisest or most workable policy, only to discern and apply the policy it did adopt. If Texas thinks good governance requires a different set of rules, its appeals are better directed to those who make the laws than those charged with following them.

During oral arguments, Chief Justice John Roberts characterized the relationship between the tribes and Texas as “each side got something, but not everything.” Roberts explained that as a compromise, tribes were willing to abide by state-law prohibition against certain gaming.

Roberts penned the dissent, which was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh. The four were unwilling to endorse Gorsuch’s interpretation of the governing law. Rather, wrote Roberts, “A straightforward reading of the statute’s text makes clear that all gaming activities prohibited in Texas are also barred on the Tribe’s land.” Roberts chastised the majority for utilizing an approach which “winds up treating gambling violations more leniently than other violations of Texas law.” Such an outcome “makes little sense,” said Roberts, “as the whole point of the provision at issue was to further restrict gaming on the Tribe’s lands,” in accordance with Texas’ long history of strict control over gambling.

The dissenting justices were overtly critical of the Ysleta’s past actions. “Although the Tribe had previously expressed its ‘firm’ ‘commitment to prohibit outright any gambling or bingo in any form on its reservation,'” pointed out Roberts, the tribe reneged in 1994 when it sought “to host a bonanza of highstakes, casino-style games, including baccarat, blackjack, craps, roulette, and more.” The Ysleta “continually pushed the [Restoration] Act’s limits,” which often led to litigation that blocked enforcement of Texas’ gaming laws.

Roberts was more than a little skeptical about the tribe’s characterization of its own “bingo” games; he detailed how inside the tribal casino, officials found over 2,000 Las Vegas-style machines that “resemble slot machines in every relevant respect.” Although Texas prohibits slot machines, the tribe insisted their machines were actually “a form of bingo,” because of the mechanism for winning.

Roberts called out the majority for employing an analysis that “leads to a bizarre result: Violations of Texas’s criminal gaming prohibitions receive more lenient treatment than all other violations of Texas’s criminal laws.”

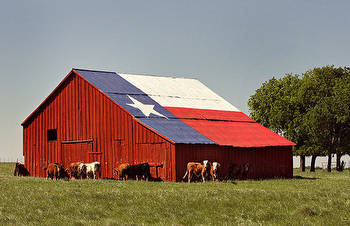

[Image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]