Times Square May Get One of the Few Spectacles It Lacks: A Casino

Times Square, New York City’s famed Crossroads of the World, could hardly be considered lacking. It has dozens of Broadway theaters, swarms of tourists, costumed characters and noisy traffic, all jostling for space with office workers who toil in the area.

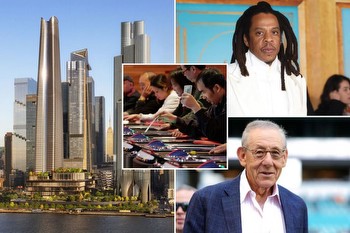

Now one of the city’s biggest commercial developers is pitching something that Times Square does not have: a glittering Caesars Palace casino at its core.

The developer, SL Green Realty Corporation, and the gambling giant Caesars Entertainment are actively trying to enlist local restaurants, retailers and construction workers in joining a pro-casino coalition, as the companies aim to secure one of three new casino licenses in the New York City area approved by state legislators earlier this year.

The proposal has enormous implications for Times Square, the symbolical and economic heart of the American theater industry, and a key part of the city’s office-driven economy. Although foot traffic in Times Square was almost back at 2019 levels during recent weekends, theatergoers and office workers have been slower to re-embrace a neighborhood where violent crime has risen.

Overall attendance and box office grosses on Broadway are lagging well behind prepandemic levels, and there is considerable anxiety within the industry about how changes in commuting patterns, entertainment consumption and the global economy will affect its long-term health.

A casino in Times Square faces substantial obstacles. There is already a competing bid for a casino in nearby Hudson Yards from another pair of real estate and gambling giants, Related Companies and Wynn Resorts.

And with casino bids also taking shape in Queens and Brooklyn, there is no assurance that the New York State Gaming Commission will place a casino in Manhattan, let alone Times Square, one of the world’s more complex logistical and economic regions.

Few things change in Times Square without notice or protest. When the city installed pedestrian plazas in the area more than a decade ago, the move was widely condemned and even lampooned by late-night talk show hosts, before being eventually embraced as an innovative foray in urban design. When the neighborhood’s army of costumed characters gained a reputation for aggressive solicitation, the city restricted them to designated “activity zones,” raising free speech concerns.

Now critics worry that putting a casino at 1515 Broadway, the SL Green skyscraper near West 44th Street, would alter the character of a neighborhood that can ill afford to backslide toward its seedier past, and further overwhelm an already crowded area.

In a copy of a letter soliciting support for the casino, which was obtained by The New York Times, the companies promised to use a portion of the casino’s gambling revenues to fund safety and sanitation improvements in Times Square, including by deploying surveillance drones.

Yet the idea of a casino has already found an influential opponent: the Broadway League, a trade association representing theater owners and producers. On Tuesday, the league sent an email to its members saying it would not welcome a casino to the neighborhood.

“The addition of a casino will overwhelm the already densely congested area and would jeopardize the entire neighborhood whose existence is dependent on the success of Broadway,” the league said in a statement. “Broadway is the key driver of tourism and risking its stability would be detrimental to the city.”

The congestion in Times Square is both a closely watched sign of vibrancy and a potential irritant, particularly for commuters and theatergoers who sometimes cite the crowds and the cacophony as reasons to stay away.

For New York, Times Square is an important financial engine — the city relies heavily on tourists to spend money at the neighborhood’s hotels, restaurants, stores and entertainment venues.

There are ample indicators that Broadway is still struggling: Several productions, including “The Phantom of the Opera,” which is the longest-running Broadway show in history, and “A Strange Loop,” which won this year’s Tony Award for best musical, have announced plans to close.

Last week, there were 27 shows running on Broadway, seen by 225,731 people and grossing $29 million; in the comparable week in October 2019, before the pandemic, there were 34 shows running that were seen by 286,802 people and grossed $35 million.

Still, the Actors’ Equity Association, the labor union representing actors and stage managers, is among those supporting the casino bid, suggesting a contentious road ahead for a proposal that will face a lengthy approval process.

“The proposal from the developer for a Times Square casino would be a game changer that boosts security and safety in the Times Square neighborhood with increased security staff, more sanitation equipment and new cameras,” Actors’ Equity said in a statement. “We applaud the developer’s commitment to make the neighborhood safer for arts workers and audience members alike.”

The simmering tensions between local power brokers, months before the formal bidding process has even begun, foreshadow the fight ahead for developers hoping to cash in on what could become the most lucrative gambling market in the country, at a time when traditional office-using tenants have become more scarce.

A state committee formed this month to review casino applications said the process would open by Jan. 6, and that no determinations on locations would be made “until sometime later in 2023 at the earliest.”

In their letter seeking support for the casino, SL Green and Caesars said that gambling revenues could be used to more than double the number of “public safety officers” in Times Square and to deploy surveillance drones.

The letter said a new casino would result in more than 50 new artificial intelligence camera systems “strategically placed throughout Times Square, each capable of monitoring 85,000+ people per day.” The safety plans were developed by former New York Police Commissioner Bill Bratton, according to SL Green.

Mr. Bratton did not respond to a request for comment.

“As New Yorkers, it’s incumbent on us to keep making sure Times Square is keeping up with the times, and doesn’t go back to what I’ll call the bad old days of the ’70s or the early ’90s,” said Marc Holliday, the chief executive of SL Green. “And we all remember what that was like, when it comes to crime, and, you know, open drug use.”

The casino is expected to include a hotel, a wellness center and restaurants, right above the Broadway theater that is home to “The Lion King” musical and a stone’s throw from the site of the ball drop on New Year’s Eve.

Earlier this year, the state authorized up to three casino licenses for the New York City region. Legislators have touted the union jobs, tourists and tax revenue that a casino would attract, citing the fact that the bidding for each license will start at $500 million.

Two existing “racinos” — horse racetracks with video slot machines but no human dealers — are considered front-runners for two of the three licenses: Genting Group’s Resorts World New York City in Queens and MGM Resorts International’s Empire City Casino in Yonkers, N.Y.

The competition for the third license features many of the country’s major casino companies. Steven Cohen, the owner of the New York Mets, has been talking with Hard Rock about a casino near the baseball team’s stadium in Queens. Las Vegas Sands has been finalizing plans for its preferred casino location in the area, and Bally’s Corporation has been scouting for a development partner.

The Wynn-Related proposed casino would be on the undeveloped western portion of the Hudson Yards, which was supposed to be completed by 2025 and include residential units and parks. Related, the developer of Hudson Yards, said it plans to fulfill all of its prior housing and public space commitments for the area.

In a private pitch deck obtained by The Times, Wynn and Related wrote that Hudson Yards, near the Javits Center, was the ideal location to target “diverse upscale” guests for a casino resort complex.

“Because it attracts the upper tier of gaming consumers, Wynn is able to dedicate less than 10 percent of its resort space to gaming, yet still generate significant gaming revenue and tax benefits for municipalities,” reads a slide in the deck.

The deck also features photos of an outdoor man-made waterfall — and of a couple enjoying cocktails while watching a cigarette-holding animatronic frog, apparently from Wynn’s “Lake of Dreams” show.

In their pitch letter, SL Green and Caesars said the casino was a “once in a lifetime opportunity to once again solidify Times Square as the world’s greatest entertainment area.”

Community support is an integral ingredient to winning state approval for a casino license.

The Broadway League’s “influence and clout and understanding of what theatergoers want is crucial to the future of Times Square, and if they’re opposing this proposal, I don’t see how it proceeds,” said Brad Hoylman, the state senator representing the district that encompasses Times Square.

But Andrew Rigie, president of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, which represents the city’s restaurants and bars, said the group would support a casino in Manhattan if it used local restaurant operators or provided vouchers to nearby eateries. A major question surrounding the economic impact of casinos is whether they incentivize guests to stay and eat inside the building, which could hurt surrounding businesses.

Alan Rosen, the owner of Junior’s Cheesecake, a restaurant chain with locations in Times Square and at the Foxwoods Resort Casino in Connecticut, said he was unconcerned.

“I can’t see it hurting my business,” he said. “Look at Las Vegas. What do people do? They eat. They go to shows. It’s a lot more than gambling these days.”