New York City Casino Competition Heats Up: The Details

A downstate casino license in New York seems to be the ace of spades for developers, with five groups having made their plans known to compete for only three available licenses.

However, the details of each project will depend upon a request for proposals expected to be issued by the New York State Gaming Commission before Jan. 6. Until then, developers will be trying to read the state’s poker face.

But this is what we know so far.

As Kenny “The Gambler” Rogers famously said, among other things, “If you’re gonna play the game, boy, you gotta learn to play it right.” So developers such as the Related Companies, SL Green Realty and Thor Equities have been stacking their bench with gaming partners to help them win one of those three downstate licenses.

Some of the requirements for the commission to approve a casino application, as of an April 2022 version of a 2013 law, include obtaining public support from community advisory committees and compliance with state and local zoning.

Although the law allowing for four upstate and three downstate casinos was passed nine years ago, there was a 10-year delay in granting the ones downstate to provide a competition-free grace period to the upstate facilities.

And the application fee? It’s not cheap, coming with a price tag of $1 million.

Thor Equities, for example, announced Nov. 22 that it is bringing on Saratoga Casino Holdings, The Chickasaw Nation and Legends in a plan for a $3 billion gambling house in Coney Island, Brooklyn.

Melissa Gliatta, chief operating officer at Thor, believes the firm could provide to Coney Island — usually a seasonal destination for New Yorkers — a year-around attraction to an underserved neighborhood.

Thor has been amassing property in Coney Island — 5 acres between Stillwell Avenue, West 12th Street, Surf Avenue and Wonder Wheel Way — for over 20 years, Gliatta said. It is, after all, the home neighborhood of Thor Equities Chairman Joe Sitt and what they believe is the most appropriate place for a casino in the five boroughs. Times Square, for example, already has an abundance of entertainment attractions, according to Gliatta.

Thor says it’s aiming to bring jobs and cash flow to the southern Brooklyn enclave, which sees its boardwalk become a ghost town during the winter months. But it’s competing against some major players.

“I think the most important thing was who we partnered with,” Gliatta said in an interview. “We gave that an enormous amount of consideration because we believe that you get one shot here, right? We had to assemble what we considered to be the best of the best team to give us the highest odds for success and winning [a gaming license].”

In terms of zoning, Gliatta says it shouldn’t be an issue. In 2009, New York City created the Special Coney Island District to turn the eastern part of the neighborhood into a year-round amusement destination.

“We do believe that we have flexible zoning that allows for a variety of different entertainment,” Gliatta said.

This plan has opponents in local leaders such as newly elected City Councilman Ari Kagan, who has been vocal in his criticism of the plan in the press, claiming that “drugs, prostitution, crime, mental health issues, suicides, depression [and] family breakups” are all side effects of the sort of casino that would hit Coney Island.

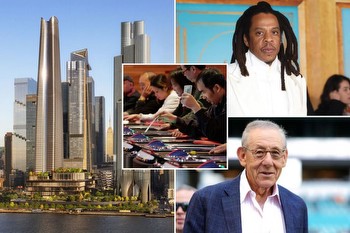

SL Green, Caesars Entertainment and Roc Nation, the entertainment agency founded by rapper Jay-Z, hope to not roll a pair of snake eyes on a redevelopment of 1515 Broadway in Times Square, despite pushback from a local theater booster group.

While SL Green declined to comment on how much floor space it would commit to gaming in 1515 Broadway, Brett Herschenfeld, managing director for the firm, said the company is not planning a large Las Vegas-style casino. Instead, SL Green is opting for a “boutique” casino on the second floor of the building, while the ground floor will continue to be dominated by The Lion King in a revamped theater space.

“The Theater District overlay, that’s where this type of entertainment use should fit and, you know, the reason why we can do a redevelopment project is because we’re not proposing a gigantic Vegas casino,” Herschenfeld told Commercial Observer. “It’s a project that fits into the context of Times Square.”

The developer of One Vanderbilt did not always see eye-to-eye with its Las Vegas parkitecture counterparts.

Caesars even proposed Roman columns and a statue of Julius himself throwing a spear, but SL Green rejected it because it did not fit the character of Times Square — which is what Herschenfeld says the project is ultimately trying to complement.

This proposal has opponents, too, though.

The Broadway League issued a letter to its members and affiliated organizations on Nov. 29, citing research behind the claim that casinos can be beneficial to underserved communities but damaging to established commercial districts such as Times Square.

The bright lights of Las Vegas or Atlantic City are not the same kind of lights as in Times Square, the organization said, leading the Broadway League to believe SL Green and Caesars were conducting an “unprecedented and dangerous experiment.”

Stating that tourism in Times Square was on track to rebound from the pandemic and exceed 2019’s level of visitors by 2023, the organization even called bull on the aspect of SL Green’s pitch that security around the gambling house would deter crime.

“For progress to continue, we remain steadfast in our commitment to preserving the unique character of Broadway — a cultural icon synonymous with New York City — and ensuring that the area is conducive to the return of tourists, business travelers, office workers and theatergoers,” the letter said. “The proposed plan to bring a casino to Times Square would introduce widespread economic and operational disruption, unprecedented congestion, and decreased safety and security.”

But SL Green is saying “et tu, Brute” to the Broadway League, which the company believes is misconstruing the partnership’s vision.

“The Broadway League is a 100-year-old enterprise. It has a lot of credibility. … But you can’t just use that platform to make misstatements,” Herschenfeld said.

To further the argument for a boutique casino, Herschenfeld explained that a 1515 Broadway casino would create a halo effect, sending customers to nearby hotels, restaurants and the other attractions of Times Square. He also hopes that it will invite New Yorkers — who typically shun Times Square as a tourist magnet — back to the Midtown business district.

In terms of zoning, Herschenfeld also believes Times Square is as good as it gets for entertainment use and signage allowances. All they need now is a gaming license.

Related picked Wynn Resorts as a partner in its bid to get permission for a casino in the undeveloped western section of Hudson Yards in September. A Related spokesperson was not available for comment by press time.

Plans to build more offices, housing and a school in this section of the mostly commercial Manhattan neighborhood were all but shelved by Related in September after months of rising interest rates, skyrocketing inflation, and a sluggish return to office following two years of remote work.

But specifics for this plan are also unclear. The developer has said it sees opportunity in placing slot machines next to the Javits Center, which last year completed a $1.5 billion expansion, and the nearby 7 train, which can transport gamblers directly from the far reaches of Queens to the doorstep of a Hudson Yards casino.

All while this is in the works, Point72 Asset Management’s Steve Cohen — who is an owner of the Mets baseball team — pitched the idea of a casino near Citi Field in Willets Points, Queens, a story that was overshadowed by the November revelation that New York City had struck a deal for a soccer stadium in the same vicinity.

The week prior to the announcement of Thor’s new partnership agreement, too, Stefan Soloviev’s Soloviev Group also revealed that it is in talks with gaming companies to redevelop a 9-acre parcel purchased by Soloviev’s father for $600 million south of the United Nations campus in Manhattan.

brett herschenfeld