Steve Wynn’s Mirage Transformed Las Vegas and the Very Idea of Luxury

Over the next week at The Ringer, in honor of the release of Woodstock 99: Peace, Love, and Rage, we will explore events that changed the world as we knew it—specifically ones that marked the ends of established eras and triggered the beginnings of then-unknown futures. Some will be overt and well established. Others will be less trodden and perhaps more speculative. But all will entertain an immovable idea that when things die, there is someone or something that pulled the trigger. Welcome to This Is the End Week.

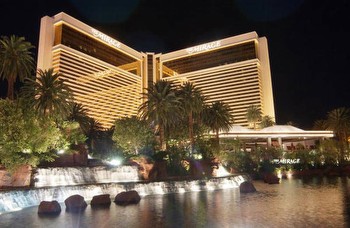

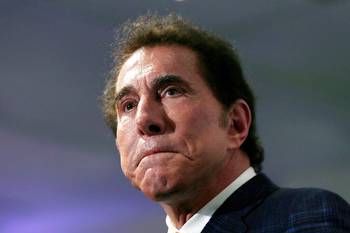

Las Vegas is a city where many otherwise cautious people have discovered many wildly incautious forms of debt, so let’s start with Michael Milken, the junk-bond king of Wall Street. In the late 1980s, shortly before he was indicted on 98 counts of racketeering and securities fraud, Milken, who was then the most powerful financier in America, helped an upstart casino executive finance his first resort on the Las Vegas Strip. Milken sold $525 million worth of bonds to cover what the executive initially thought would be $565 million in construction costs. Shockingly for a major construction project in Nevada, the resort went over budget; it finished somewhere north of $600 million. That was how Steve Wynn built the Mirage, the casino that transformed Las Vegas.

From the outside, the ’80s looked like a bad time to be plowing money into the Strip. The city’s casino industry had been crumbling for years, hit hard by the double-dip recession of the early ’80s and the legalization of gambling in Atlantic City. On November 21, 1980, a fire had ripped through the MGM Grand, killing 87 guests; word got out that Vegas wasn’t safe, and that Nevada’s famously light touch when it came to regulations meant there weren’t even fire sprinklers in buildings where, let’s face it, someone could be assumed to be smoking in bed basically 24 hours a day. The bad PR from the fire didn’t help, either, especially after another fire broke out at the Hilton. There were 300,000 fewer visitors to Vegas in 1982 than in 1980, room occupancy plunged from 77 percent to 70 percent, and the annual migration of American quarters into desert slot machines started to look like something David Attenborough would get mournful about in a nature documentary. Hotel operators slashed their prices and ripped amenities out of rooms. “No frills” is the word you see in write-ups of this era. A lot of gaming executives were like, well, let’s build RV parks and keep our fingers crossed.

A junk bond, by the way, is a bond that a credit rating agency thinks has a good chance of not being paid back. When you buy a bond, you’re loaning the money to the seller, who promises to repay you on a set date. Credit agencies look at these loan instruments and score them based on how likely the seller is to actually do it. If the bond looks safe, i.e., you probably won’t get sent straight to voicemail after the managing partner flees to Bolivia, it gets an investment-grade rating. If the bond looks unsafe, i.e., the analyst has some qualms about the loaded .38 and stack of fake passports in the CFO’s desk drawer, it gets rated below investment grade: a junk bond. Investors sometimes get excited about junk bonds despite the risks involved, because if they do pay out, they’re worth more. You get a higher yield for flirting with the odds you’ll lose everything.

Does that—I don’t know—remind you of anything? Does it maybe vaguely recall a certain pastime associated with a particular desert city? Wynn’s resort, which opened on November 22, 1989, nine years and one day after the MGM Grand fire, couldn’t have been built without Milken’s help, a fact Wynn readily acknowledged. In 1995, he was named Casino Executive of the Year by Casino Executive Magazine—a publication that not only exists, but is also, year by year, probably a better chronicle of the American mind than the New York Review of Books—and he said, speaking of Milken: “Mike is the one who changed us. No Mike, no Mirage.” The casino industry, in other words, was transformed by the Wall Street equivalent of a 3 a.m. bachelor-party blackjack table. This was a couple of decades before credit default swaps made everyone realize that a 3 a.m. bachelor-party blackjack table was a significantly more prudent and rule-abiding space than the financial sector itself.

What made the Mirage different from other Vegas casinos—what made Wynn’s vision of the Strip compelling to Milken and his clients—was that it existed primarily to be spectacular. The Wikipedia page for the Mirage notes—in the same paragraph—that it was the first resort ever financed by junk bonds and that real gold dust was used to tint the windows; these facts are deeply linked. Old-guard Vegas executives like William G. Bennett, the longtime president of the Circus Circus empire, had been trying for quite a while to attract middle-class families to the city, but they’d been operating as if the middle-class American family were a rational entity swayed by low prices and familiarity: come to Vegas, eat at Denny’s. Wynn understood that what middle-class tourists want from a gambling destination is the feeling of escaping from the middle class. The attraction of a gambling resort is not that it caters to middle-class logic but that it enables the suspension of it. We’re happy to keep losing as long as we feel like we’re winning. The Mirage was conceived as the gambling resort of the future, and the gambling resort of the future had to do something more complicated than just offer the tantalizing possibility of striking it rich. It had to coax its customers into feeling they’d already struck it rich, while actually making them poorer all the time.

So: Give them spectacle, size, dazzle. Show them the world, literally, through gold dust. At the time it opened, the Mirage was the largest hotel on Earth. It can be hard to remember this, because subsequent Vegas resorts (including several of Wynn’s: the Wynn and the Bellagio) have gone even farther down the hallucinatory-luxury path, but in its early years, the Mirage was unlike any hotel Vegas had ever seen. It wasn’t just neon and showgirls. It was magic and white tigers (Siegfried and Roy operated out of the Mirage for years, until Roy was nearly killed by one of his own big cats) and contortionist acrobats (Cirque du Soleil first played Vegas in a tent in the Mirage parking lot). It was all the food and drink you wanted. It was total sensory surfeit, so hypnotic you barely heard the cash registers ringing.

For a young city, Las Vegas has had a lot of eras. Everyone agrees that there’s a “new Las Vegas” and an “old Las Vegas,” but what those terms signify depends on who you ask. The pioneer Las Vegas, which was mostly ranchland and a Mormon fort occupied by Union troops during the Civil War: That’s one version of the old Las Vegas. Another is the city between 1905-1931, after it was officially incorporated but before the Hoover Dam, which brought plentiful water and the legalization of gambling, which brought everything else. Still another version of the old Las Vegas is the Glitter Gulch era, centered on the Fremont Street casinos, before the Strip opened and the gamblers moved south. (One of the richest Las Vegas ironies—which is saying something—is that the Las Vegas Strip is not actually in Las Vegas, but in the unincorporated city of Paradise.)

It’s the opening of the Mirage, though, that represents the real dividing line between the old Las Vegas and the new Las Vegas, because it’s the Mirage that changed the idea of “Las Vegas” into what it is today. After November 22, 1989, the whole range of possibilities was different. Before the Mirage, Las Vegas is the cowboy sign, Frank Sinatra, maybe Elvis, maybe a fight at Caesars Palace; afterward it’s the Eiffel Tower and the giant hot air balloon and Celine Dion and Britney Spears.

The nature of American opulence is to move from elegance toward comfort. Before the Mirage, Vegas means relatively well-dressed people in relatively drab interiors; after, it means schlubs in astonishing movie sets. The nature of American pleasure is always to move from adulthood toward childhood. Before the Mirage, Vegas is pretty frankly about gambling and drinking and sex; after the Mirage, it dilutes its hedonism by setting it inside fantasyland castles filled with circuses and fountains and cosplayers in Spider-Man suits who’ll take a selfie with you for $5.

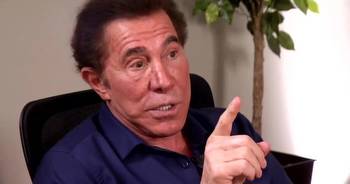

A project on the scale of the Mirage is polarizing whether or not it succeeds, and the Mirage succeeded wildly. Even at the time, reports about how Wynn’s vision was changing the gambling industry tended to see the resort as an inflection point. Take the 1996 Washington Post profile of Wynn by Blaine Harden and Anne Swardson. Harden and Swardson depict the Mirage as transformative in two ways: first, as the moment when Wall Street went all in (sorry) on gambling; second, relatedly, as the moment when gambling truly broke away from organized crime. After the Mirage, they write, Wynn was able to finance his resorts with safer instruments than junk bonds—things like bank loans and stock offerings—because Wall Street sold the industry to respectable institutional investors; by ‘96, the endowment of Harvard University had a $38 million stake in gambling companies.

Wynn had once been accused of having problematic mob ties—a Scotland Yard investigation in 1982 called him a front for the Genovese crime family, and a New Jersey investigation had caught the director of his Atlantic City casino hobnobbing with “Fat Tony” Salerno, reputedly the Genovese family boss—but now he was being exonerated by regulators. Around the same time that Wynn was hosting a gathering of Wall Street money managers at the Mirage to talk about investing in the casino business, the chairman of the New Jersey Casino Control Commission announced that there was “simply no basis” to the allegation that Wynn was connected to the mob. (Wynn himself always denied any connection and issued a lengthy rebuttal of the Scotland Yard report, which he called “erroneous, misleading, and false in every respect other than the spelling of my name.”)

Las Vegas as legitimate business, Las Vegas as a luxury consumer experience, Las Vegas as a place to eat world-class meals and be mesmerized by flashing lights and browse $8,000 suits at the Kiton boutique in the mall at the Venice casino (which is of course designed around a simulacrum of Venetian canals): all that starts with the Mirage. And the old Las Vegas, the Vegas of Moe Greene and scotch on the rocks and showgirls in ostrich feathers and Dean Martin in a tux with the tie undone—that version of the city fades out as the Mirage’s lights come on. Vegas has wavered through the past 30 years about whether it wants to be family-friendly or not. What hasn’t wavered is the consumer gloss that the Mirage drizzled onto the city—the sense that you could go there to feel special, not just to feel good.

It’s a funny place, this country. It’s not just in Las Vegas that the difference between winning and losing tends to blur in the presence of money. The mirage of the Mirage seems to get bigger all the time. Remember how I said Michael Milken, the resort’s financier, had been indicted for racketeering and securities fraud? Well, five months after the Mirage opened, he pleaded guilty to six of the original 98 counts. He paid a $600 million fine and was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison. The case was notable in part because the prosecutor whose investigation nabbed Milken was a hard-charging New York attorney who used the conviction as a springboard to a political career. His name was Rudy Giuliani.

Giuliani became the mayor of New York City. Milken, who got out of prison after serving less than two years of his 10-year sentence, remained a billionaire. On December 26, 2000, The Wall Street Journal reported that the two men were having lunch together in Manhattan. At the time, Giuliani was pushing for a presidential pardon for Milken, in recognition of his contributions to cancer research. George W. Bush wouldn’t touch the case, and neither would Barack Obama. But 20 years later, on February 18, 2020, Milken got his presidential pardon from Donald Trump. The president of the United States, it transpired, had sold nearly $700 million worth of junk bonds in the late ’80s, money he used to finance the construction of the Trump Taj Mahal during his time in the casino industry.