How Steve Wynn, The Mirage changed the way Las Vegas casinos were financed, built

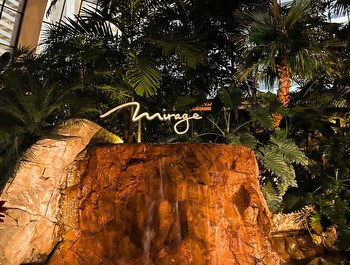

The Mirage hotel-casino is often cited as being a trailblazer and the first true mega resort in Las Vegas. The “Oasis in the Desert” changed the way casinos approached the business of making money and how the outside world perceived Las Vegas.

However, Steve Wynn’s creation, which came to life in 1989 and will close for good on July 17, also reset the industry standard for how pie-in-the-sky casino concepts become reality. For all the other accolades and recognition bestowed upon The Mirage, it should also be remembered as the property that became the industry model for how to raise money to build casinos.

David Schwartz, gaming historian and UNLV ombudsman who previously worked as director of the university’s Center for Gaming Research, said Wynn’s ability to secure more than $600 million in financing for the project when “Las Vegas mostly had $200 million casinos at that time,” is nothing short of “extraordinary.”

Financing through junk bonds

“Probably hundreds of people have had ideas for casinos in Las Vegas or Atlantic City or anywhere else, but if you can’t get the money, you won’t ever get it built,” Schwartz said.

The Mirage was not the first gaming property to be funded with high-yield bonds, or, as they are more derisively called, junk bonds. Nor was it even Wynn’s first go around at securing speculative, high-risk bonds to finance a casino project.

But Wynn’s ability to convince Wall Street that his ambitious casino ideas would bear fruit is nearly as consequential to the gaming world as the properties that resulted from his salesmanship. And, the success of his junk bond-funded casinos gave way to a new financing model that has been copied across the gaming landscape for decades.

Golden Nugget Atlantic City was Wynn’s initial foray into using high-yield bonds. Wynn and Michael Milken partnered to open the Boardwalk casino property (not to be confused with the Marina District casino that is now called Golden Nugget) in 1980.

Dan Heneghan, retired New Jersey Casino Control Commission spokesperson and current industry consultant, was a gaming reporter at The Press of Atlantic City when the Nugget was being built. He recalls getting a GNAC press release about the project raising roughly $160 million in secured senior sinking fund debentures.

Heneghan also remembers not having the “foggiest idea” what that meant.

After talking to the chief financial officer with the GNAC for 45 minutes or so, and still not understanding the jargon, Heneghan contacted a friend in the financial services industry who explained the concept in layman’s terms in a few minutes. While the terminology was complex, the meaning behind it was now clear. Wynn and Milken would use high-yield bonds to fund the construction of the Atlantic City casino.

“Steve Wynn pioneered the use of junk bonds to finance casino construction here in Atlantic City, and he did it with the help of Mike Milken,” Heneghan said. “Although, it’s probably the other way around (because) Mike Milken had already been deeply involved in financing things for companies with junk bonds, raising money for various projects by structuring junk bond deals.”

Milken is sometimes referred to as the “junk bond king,” because of his use of the high-risk, high-reward financial model. Milken would later be convicted of financial crimes and served time in prison before receving a pardon from former President Donald Trump in 2020. Milken is listed as one of the world’s wealthiest individuals and, since his release from prison, has turned to philanthropy.

Wynn and Milken’s AC casino gamble paid off. Despite being the second-smallest casino property in Atlantic City, the Golden Nugget became the market’s top-earner in 1983. Wynn sold the property in 1987 for somewhere between $440 and $470 million.

Right around that time, Wynn turned his sights back to Las Vegas. Wynn already owned the Golden Nugget in downtown Las Vegas, and its success fueled his desire to expand. He added two hotel towers to the Nugget in downtown; one in 1984 and the other in 1989.

But the idea for The Mirage was on another level.

In order to satiate an increasingly more affluent demographic visiting Las Vegas, Wynn embarked on The Strip’s most ambitious concept to date — the 3,000-plus room Mirage, which featured a giant exploding volcano out front, live exotic animals and, eventually, year-round entertainment that attracted guests who were not always interested in gambling.

The project was funded with junk bonds, which scared Wall Street. No other casino project had ever come close to the $630 million price tag attached to Wynn’s creation.

The Mirage opened on Nov. 22, 1989 and was instantly a commercial and financial success. According to industry data, visitation to Las Vegas increased 16 percent in 1990, which remains one of the largest year-over-year increases, percentage-wise, in the city’s history.

Wynn rebuffed the doubters

Analysts at the time predicted The Mirage would need to exceed $1 million a day to satisfy its debt obligations. It did so with ease.

In a 1996 interview with CNN Money, Wynn rebuffed the early doubters of The Mirage by saying,”How could anyone understand Disneyland if all they’d ever seen was the Santa Monica pier?”

Wynn’s use of junk bonds to finance the ultra-successful Mirage produced countless copycats all over the country.

“It opened up financing for a lot of other casinos, especially when people saw how successful the Mirage (was),” Schwartz said.

Heneghan, who has nearly 50 years of gaming industry experience, said junk bonds became a “very effective tool” for casino developers.

“Wynn was really the first one to use (junk bonds) at any significant level,” he said. “By getting involved with junk bonds, which were very risky, casino companies were able to raise a lot more money for whatever kind of projects they wanted to build. So there (have been) lots of very large scale casino projects built with junk bonds.”