Should Cambodia Ban Casinos?

To quickly answer the question posed in my headline: not yet. But the Cambodian government needs to at least put this possibility on the table, to set a fire under the feet of the casino owners. A statement must be made by Phnom Penh that casinos have less than 12 months to turn the current dire situation around. If they fail, then regular gambling should go the way of online gambling, which Prime Minister Hun Sen banned in 2019.

Phnom Penh ought to be humiliated by recent events. Last week, video footage emerged and quickly went viral, showing dozens of Vietnamese nationals literally fleeing a Kandal province casino where they’d reportedly been held in slavery. The people flee the casino and try to swim across a river back to Vietnam. According to some reports, a 16-year-old drowned. (This took place whilst the new United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia, Vitit Muntarbhorn, was making his maiden visit to the country.) Thanks to some fantastic reporting in recent months, we know this isn’t the only (mainly Chinese-owned) casino in the country accused of forced labor. Cambodia’s coastal city of Sihanoukville has changed beyond recognition. Crime has spiked. The city’s now a byword for the social chaos caused by rapid investment in a seedy sector.

At the same time, laid-off workers at the NagaWorld casinos in Phnom Penh have been protesting since December 2021 over layoffs, which they claim are efforts by the Malaysian-owned firm to destroy their trade union (the only Cambodian union representing casino workers). They were finally able to demonstrate outside the casinos this month during Vitit’s visit, although many of their strikes resulted in police brutality. And then there are the things that everyone knows but has grown tired of repeating: the countless gamblers who have committed suicide at the casinos; the corruption; the land rights violations; the social and environmental costs.

How bad does it have to get before the government really acts, not just with warnings or commitments but with action? Even for self-seeking reasons. Cambodia is getting an image as a country where modern-day slavery flourishes, where trafficking syndicates have gone unpunished for too long. The U.S. added Cambodia to its trafficking in persons blacklist in July. Taiwan’s government this month issued warnings. Its authorities have said that they know of 5,000 citizens traveling to Cambodia and not returning. The Guardian, a British newspaper reported that hundreds of Taiwanese had been “trafficked to Cambodia and held captive by telecom scam gangs.” In recent days, Vietnamese media has reported frequently on the topic. On August 26, they reported on a Vietnamese national who was beaten to death outside a Cambodian casino. Another report, from the same day, was headlined: “Man sells son’s friends to Cambodia.” One Malaysian commentator put it this week: “Of late, we have been fed by the media with too much of sickening news on modern slavery perpetrated in Cambodia.”

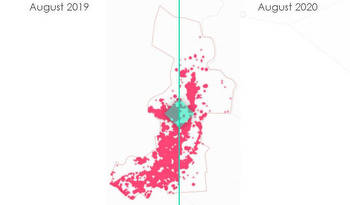

The natural response is there are major problems in every sector and no one wants to ban them. Yet there are differences. We have the utterly contradictory situation where Cambodians themselves cannot enter their own country’s casinos to gamble, yet they can serve drinks or flip cards for foreign gamblers. More importantly, there’s precedent. In 2019, Hun Sen, the prime minister, intervened to ban online gambling in Cambodia. If one recalls, it was that decision that led to an exodus of Chinese nationals from the country the same year. Bradley Murg, an analyst, dubbed it the “Great Chinese Exodus of 2019.” Within two weeks of Hun Sen’s announcement, some 120,000 Chinese had left. By one estimate, land prices in Sihanoukville collapsed by 25 to 30 percent in the wake of the ban. The COVID-19 pandemic largely masked this fact. No doubt, Hun Sen was moved by stories of the victims of these scammers. But it was also politically motivated. He had to do something about the growing public frustration about crime in Sihanoukville, a by-product of the online gambling syndicates. Also, the pressure was most likely applied from Beijing, since the majority of those being scammed by the online gambling rackets were Chinese nationals back at home.

It’s time for some honest debate. Have casinos been good for Cambodia? On the social front, the answer is a clear no. Many Cambodians reckon Sihanoukville has been utterly gutted by the casino boom. Crime has spiked. Locals have been outpriced. Many will no longer go to the city, previously a popular location for weekend getaways. Casinos have tarnished Cambodia’s reputation and that of legitimate businesses. No doubt they have exacerbated Cambodia’s already rife corruption. All this, for some, could be justified if the finances made sense. Developing countries, naturally, have to pinch their nose when it comes to some ways of making money. Cambodia’s economic growth over the past two decades, after all, has chiefly come from selling the cheap labor of its workers in the garment sector. Perhaps one could justify the gambling sector’s detritus if it was a big job-creator, if profits were pumped back into the local economy, and if it was taxed to the hilt to fund state welfare for Cambodians.

Most of the country’s casinos are foreign-owned. NagaCorp, which has an exclusive license to run casinos within a 120-kilometer radius of Phnom Penh, is owned by Malaysian-Chinese businessman Chen Lip Keong and is publicly listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. By far the country’s largest casino, including a hotel and resort, it was estimated to have employed 8,371 workers before mass layoffs in 2020. A small casino would probably employ a hundred or so workers, the same as a small garment factory. Of course, there are additional jobs and economic benefits of gambling tourists who arrive and spend their money outside the casinos, yet the data suggests those benefits are limited. And there’s no certainty those visitors will return in similar numbers post-pandemic. Nor does it mean it’s the route Cambodia ought to take. During the pandemic, there was much debate about whether Cambodia should even want to see the return of mass tourism or whether, instead, it should change tack and try to focus on attracting fewer but higher-spending visitors. In the long run, the latter makes sense. I don’t want to unnecessarily enrage Cambodian patriots but you can’t have it both ways: either Cambodia’s natural beauty and culture are enough to attract tourists or they aren’t. The claim that Cambodia needs casinos to attract Chinese visitors is as cynical as it is self-serving.

Under the Law on the Management of Integrated Resorts and Commercial Gambling, introduced in 2020, casinos are supposed to pay a 7 percent tax on mass gross gaming revenue and 4 percent on VIP operations. Has this been a “robin-hood tax,” taking from (wealthy) casino owners and giving back to the Cambodian state? The pandemic has complicated the numbers. The Commercial Gambling Committee of Cambodia, part of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, recently said it had only collected just 8 percent of the expected amount in the first six months of this year (and most of that was from lotteries and raffles). But that expected revenue goal for the whole year (which now doesn’t look like happening) was only $43.5 million. In 2019, before the pandemic and the new gambling tax law, only $85 million was taken in casino taxes, which fell to $40 million in 2020. Granted, the law change in 2020 ought to increase tax collection once the gambling sector is back up and running but it’s hardly going to be a major contributor to state revenue. The General Department of Taxation, which is in charge of domestic taxes, collected $1.9 billion in taxes in the first half of this year alone.

In one way, the government seems to be sticking to old ideas. Mey Vann, a secretary of state at the ministry, has : “After the government released tourism recovery strategies and aviation reopening, [the casinos] probably hope that they would be able to see more tourists coming.” Other comments from ministers suggest they want the status quo ante: vast numbers of Chinese tourists piling into Cambodia’s casinos once Beijing ends its ridiculous “zero-COVID” policy. On the other hand, in June it was reported that only 20 casinos, out of more than 200, were operational. The Finance Ministry said last week that it has renewed licenses for 63 casinos this year. It was reported in mid-July that 143 had reapplied for licenses. (Licenses are regranted annually.) The lack of new licenses, one suspects, is partly explained by the authorities improving their inspection. Let’s see how many licenses are renewed by the close of 2022.

Honest debate is hard. The Phnom Penh government, especially because of its closeness to Beijing, won’t want to target a largely Chinese-owned and operated sector. Certain newspapers are tied to casino operators. We haven’t even mentioned the corruption that lies at the heart of the gambling sector. Many important people in Cambodia are getting fat from it. But things are at a point of no return. Serious and meaningful change needs to happen. The authorities need to start cracking down. The crime syndicates must be made aware that the police won’t look the other way anymore. Cambodia’s reputation is being damaged. Cambodians can’t be happy their country is in the international news for all the wrong reasons. Foreign governments, including those of vital importance to Phnom Penh, aren’t pleased about how their own nationals are being treated in Cambodia. But if that change cannot happen, the debate needs to turn to prohibition.