‘No way out’: how video games use tricks from gambling to attract big spenders

One evening in April, Carrie* sat down and wrote a suicide note to Zynga, the maker of mobile phone games such as Farmville and Words With Friends.

Carrie had been spending uncontrollably on one of Zynga’s less well-known apps, Wizard of Oz Slots, a game that mimics casino slot machines but with no payout available.

A recovering gambling addict, she had used a national self-exclusion scheme to bar herself from online casinos. There is no such scheme for computer gaming.

Carrie had begun playing obsessively through the night, spending thousands of pounds in the game and racking up huge debts. She craved dopamine, a chemical released by the brain that exacerbated by her ADHD. Where once she got her dopamine hit from online casinos and fixed-odds betting terminals (FOBTs), she now had mobile gaming.

“Zynga deliberately uses the same techniques that bookmakers do with slot machines to feed people’s addiction and now I find myself addicted with no way out,” she told the company.

Zynga agreed to lock her out of her account but, Carrie says, she was able to log back in a couple of days later. She still struggles to rein in her spending.

Carrie had good reason to compare the seemingly benign world of mobile phone games to the more overtly controversial gambling industry, for the two pastimes are rapidly converging.

In 2016, the chief executive of the game developer Tribeflame, Torulf Jernstrom, outlined the “tricks” that the mobile games industry, soon projected to be worth $100bn (£76bn) a year, could use to part gamers from their money.

Addressing a conference in Helsinki, he briefly touched on the morality of this, saying: “We can discuss it, if we have time, later.”

Examples included exploiting a player’s “hot state”, an impulsive mood created by game dynamics, giving them a time-limited opportunity to spend hard currency to progress.

Another was to offer an in-game item for nothing and then threaten to take it away unless players paid, capitalising on the human trait of “loss aversion”.

Or why not exploit the “herd mentality” by publishing details of what rival players are spending? Whatever you do, it is “poison” to admit that the vast majority never spend anything at all, Jernstrom said.

Since his provocative speech, mobile phone gaming has exploded, turbocharged during the pandemic when households were trapped at home during rolling lockdowns. Between 2016 and 2018, revenues doubled from $27bn to $54bn, according to gaming analysis firm Newzoo. They stagnated in 2019 but soared again when lockdowns kicked in, with the $100bn barrier due to be breached by 2025.

Jernstrom’s aim, he told the Guardian, was to be “provocative”, to spur honest debate about the tactics that some companies were using in this rapidly growing arena.

The title of the talk, Let’s Go Whaling, offered insight into how gaming companies had learned to ape gambling.

A whale, in gambling, is someone who consistently wagers large amounts, a lucrative target for rival poker players, bookmakers or casinos.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the techniques described in Let’s Go Whaling bear comparison to some of those that bookmakers and casinos have long deployed, capitalising on deep understanding of psychology.

The big difference, of course, is that the gamer can never win money, only prestige or progress in a virtual game.

Yet a small but lucrative minority of players are happy to spend on something that, to them, does have value, even if it is not monetary.

The holy grail is to convert just some of the legions of free-to-play gamers into these premium players, to make them into whales.

In the UK, the gambling regulator has forced operators to rein in “VIP” programmes that incentivised betting and stoked addiction, after political and public pressure. At the same time, gaming firms have quietly ramped up their own schemes.

Carrie’s email chain with Zynga showed that the company considered her a VIP – little wonder when her Monzo bank account showed that she spent almost £7,000 in little more than a year on purchases in Google’s Play Store.

In a recent interview, Zynga’s vice-president of player succcess, Gemma Doyle, referred unabashedly to internal models that identify people who are on course to spend high sums.

Should they reduce their outlay, she told GamesIndustry.biz, the company would “reach out and call them to find out what’s wrong”. She went on to describe pressure-selling practices that are increasingly taboo in the British gambling sector but remain unregulated for gaming firms.

Lies van Droessel, a games researcher at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, has spent years studying the production of games, especially mobile free-to-play games.

At the top of the industry, she says, most companies are wary of being too aggressive in how they monetise players.

“What they really try to do is give people the feeling that it’s fair, so they don’t have the feeling they’re being taken advantage of,” she says.

“Candy Crush, for instance, has a very casual audience, the percentage of paying players is likely to be below 10%. But they have so many players that if 1% more spend €1 more, it’s a huge advantage.”

But some of her interviewees spoke of less benign tactics at the margins of the industry and particularly in the “wild west” days of its early development.

At one company, an employee told her, executives sometimes grew concerned about the ease with which players were progressing through the game without paying.

They would ask designers to add a fiendishly difficult “bottleneck” level that would be all but impossible to pass without spending money.

A separate source in the game design industry told the Guardian of one studio that openly boasted during a conference, of tweaking the supposedly “random” number generator that powered outcomes in its game.

By doing this, it could ensure players won bigearly on, to give them a taste for the game, then dial down their chances later, creating an incentive for them to spend money to progress.

An early win is a well-documented technique known among gambling researchers and clinicians as a catalyst for addictive play, because it creates an early dopamine hit that gamblers are then eager to recreate, even as their subsequent losses mount.

A gambling operator that orchestrated this outcome would probably lose their licence to operate in Britain but there is no clear disincentive for gaming firms.

Gambling tends to spur much greater ethical concern and regulatory scrutiny, yet overlap – in practice and even game design – is becoming increasingly evident.

CoinMaster, owned by the Israeli company Moon Active, consistently ranks among the world’s most popular mobile games, with lifetime revenues since 2015 of $3bn and well over 100m downloads.

To progress, players spin a casino-style “slot machine” to earn coins that can be used to build their own virtual village. It was previously age-rated 4+, although that has now increased to 12.

As popular as the game is, reviews on the Android Play Store and Apple Store focus on one key irritant.

“My biggest complaint is that the higher level you are, the more it becomes impossible to advance or even enjoy the game without spending money,” one reads.

This is increasingly true in more traditional console-based video games too.

Perhaps the most visible example of the point at which games and gambling collide is in the emergence of loot boxes and skins betting, gambling-style features that have become increasingly common in video games.

Loot boxes contain mystery in-game items, such as weapons or outfits, that can be obtained for money, without knowing what the player will get. They have become increasingly popular due to their power to transform revenues.

Now, instead of a one-off transaction that exchanges, say £40 for 100 hours of gaming enjoyment, firms have found a way to encourage repeat revenue streams. This generates $15bn a year, about 90% of which comes from a small group of whales.

Matt*, a 38-year-old data analyst from the north-west, is one. Like Carrie, he self-excluded from gambling but found there was no option to do so from gaming.

He has spent well in excess of £10,000 on player packs in the Fifa football game, where players can buy loot boxes that contain mystery footballers. Bundles of points to spend on loot boxes sell for as much as £87.99.

He likens the feeling to betting on FOBTs, which were curbed in 2019 after public outcry about addiction.

“You become detached from reality and your focus is on trying to get the players,” he says. “You almost switch your brain off from thinking about normal things. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the same processes and behaviours [as gambling].”

Like Carrie, he has begged gaming companies for a self-exclusion option, to no avail.

EA Sports, which makes Fifa said: “We design all our games to provide experiences that offer choice, fun, fairness and value and believe that optional in-game purchases, including loot boxes, when done right play an important role in giving players choice in how they want to invest in a game, be that through time or money. EA and the video games industry are engaged in many efforts to provide information, awareness and control to players and parents around the robust controls that can be used to limit or restrict purchasing.”

Successive studies have found links between problem gambling and loot boxes. Yet, because players cannot usually cash out and turn their winnings into money, such features are not regulated as gambling.

Another recent piece of research concerned skins, a common feature of games such as Counter Strike. They can be used as virtual currency by people who want to bet on the outcome of competitive video games.

The study found that skins betting was one of the most reliable predictors of problem gambling, comparable to heavily addictive fixed-odds betting terminals (FOBTs).

Last year, the then culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, announced the results of a consultation into gambling-style features in video games. The consultation, she said, had found an “association between loot boxes and harms” but there was no proof that the link was causative.

Mindful of potential “unintended consequences”, Dorries said, the government would take no action, relying instead on the industry to work on improving its self-regulation.

An update on how the industry’s plans to regulate one of its most lucrative inventions is expected soon.

Daniel Wood, joint chief executive of gaming industry body Ukie, said gaming firms had developed tools including “clear and easy-to-use parental controls to help manage screen time, in-game purchases, including loot boxes, online interactions, and access to age-appropriate content”.

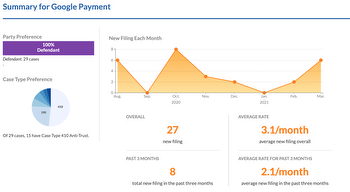

Zynga and Google declined to comment.