Time to clamp down on video game ‘gambling’

But increasingly, young gamers today find themselves addicted to risky games of chance, throwing away money on virtual in-game items to feed a gambling-like habit.

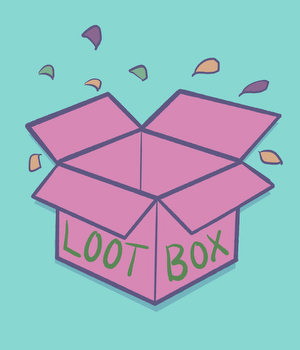

In bedrooms and living rooms up and down the country, young people are being lured into casino-like features on video games. On mobile phones, computers and consoles, gamers are enticed into squandering money on so-called “loot boxes”.

Many popular modern games feature loot boxes. Gamers use real money to purchase a virtual mystery box in the hope of getting an advantage, like a playable character, weapon, or cosmetic feature.

Cough up some money, and that box might include something valuable that can be traded on a secondary market for cash. Or it might unlock something with little value, tempting you to part with more money and roll the dice again.

Gaming forums highlight concerns over the virtual products. Kiwi Redditors describe loot boxes as “gambling for gamers”. Another likens them to “a Kinder Surprise. Gambling for toddlers”. One gamer tells a story about “a mate who spent $1300 on in-app purchases on a mobile game one weekend”.

The global gaming industry is estimated to make about $25 billion from loot boxes per year, comprising one-quarter of its total revenue. The in-game items have become a central part of mainstream gaming, with developers and platforms raking in a fortune in additional income.

Game developer Valve, and its online publisher Steam, is regarded as one of the pioneers of loot box gaming, through titles such as Counter Strike: Global Offensive. Valve’s owner, American billionaire Gabe Newell, moved to New Zealand during the pandemic and has applied for residency here.

There are growing concerns that modern games give young people an early introduction to gambling, using their parents’ stored credit card details.

Across the Tasman, a report released this week by the New South Wales Office of Responsible Gambling revealed that children as young as 11 play video games and apps that simulate betting. A total of 40 per cent of children in the state have played the games.

Meanwhile, a study published today by Massey University has found that problem gambling symptoms are associated with greater loot box spending. The association was found to be stronger for people in quarantine and isolation environments, indicating that more people with problem gambling symptoms were spending money on loot boxes during lockdown.

The rapid rise of loot boxes, and the ability to monetise and trade them in some instances, has prompted calls for stricter regulation and age controls.

Loot boxes are a grey area for New Zealand regulators. While NZ has relatively strict laws on traditional gambling, video game items are not covered under the Gambling Act 2003.

As developers cash in on loot boxes and in-game purchases, experts are calling for parents to keep a closer eye on their children’s gaming habits.

Massey University’s Dr Aaron Drummond says: “The key message is to do your research. Ask your kids to show you their game so you can see what is purchasable for real-world money. Make sure you put controls on your credit card details to stop unwanted spending.”

Drummond says loot boxes have “all the hallmarks of gambling”, and believes age restrictions on games, or clearer labelling for parents, could help to reduce harm.

The international regulatory treatment of loot boxes varies.

The Netherlands has taken a hardline stance. In October, courts in the country hit FIFA publisher EA Sports with a €10 million (NZ$167m) fine for its loot box features. EA denies that its purchasable “packs” constitute gambling and is appealing the ruling.

An Australian House of Representatives committee has called for the nation’s government to impose greater restrictions on loot boxes. In the UK, a House of Lords Gambling Committee has called for the boxes to be brought under traditional gambling legislation and regulation.

Our government is yet to confirm its stance. The Department of Internal Affairs has stated that loot boxes do not fall under the Gambling Act 2003. But the department is looking into games as part of its review of the online gambling industry.

The Problem Gambling Foundation is calling for faster action on the issue after launching an awareness campaign on loot boxes.

The PGF’s Andree Froude is concerned about the “gamblification” of the gaming industry. She says 32 people approached the organisation over loot box issues in 2020, a far higher number than previous years.

“These games feature simulated gambling,” she says. “Gamers don’t know what they are getting when they are buying a loot box, and it is risky. We’ve heard stories of people spending thousands on credit cards. It would be good if these games were restricted to a certain age group.”

The dangers of loot boxes show that our laws need to evolve with the times. With more young people and children getting hooked on games of risk, the government should regulate these video game features, especially those that offer tradable and sellable in-game purchases.

While video games were harmless once upon a time, times have changed. Today’s titles clearly pose a far greater risk to young gamers. Developers should accept greater responsibility for their products, and governments should hold them to more scrutiny.