Closing for good on April 2, Tropicana Las Vegas leaves behind a legacy of showmanship and reinvention

The Tropicana is dead; long live the Tropicana. The storied hotel-casino closes its doors April 2, just two days shy of its 67th birthday, to make way for a Major League Baseball stadium and a new Bally’s resort. Over the next year, the land the Tropicana now occupies will be cleared, with the intent that the organization currently known as the Oakland A’s will claim the empty lot in April 2025 and begin to build.

The Tropicana is survived by Caesars Palace, Circus Circus, the Flamingo and the steadily dwindling number of pre-1970 Las Vegas Strip resorts that haven’t been imploded, rebranded or remodeled to the point of being unrecognizable. And though there are plenty of sound financial arguments to be made for leveling the Tropicana, it’s nonetheless heartbreaking to watch another Vegas original disappear, with little for locals to do but consider its legacy.

“New things are always good for Las Vegas. And the baseball [stadium] is going to be great,” says Harry Basil, partner and general manager of Laugh Factory, a Trop fixture for a dozen-plus years.

He adds, wistfully, “I just wish it was somewhere else.”

The Tropicana was the brainchild of Ben Jaffe, a Miami hotelier who owned the land underneath the hotel, and Phil Kastel, an organized crime figure whose company built and operated the resort. At opening, the 325-room Tropicana was Vegas’ most expensive property at a cost of $15 million—over $470 million in 2024 dollars. A 60-foot-tall, tulip-shaped fountain stood at the property entrance; inside, its luxurious Caribbean-inspired décor earned it the nickname “the Tiffany of the Strip,” a title befitting a jewel.

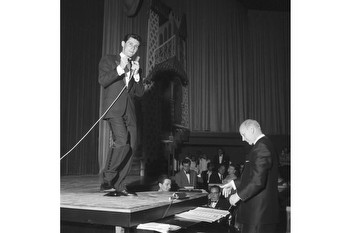

Glory attached itself to the Tropicana almost immediately. Big-band greats the likes of Errol Garner, Benny Goodman and Gene Krupa performed there in its early years. Several iconic movies and television shows, including the Elvis Presley musical Viva Las Vegas, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part II, the James Bond vehicle Diamonds are Forever and a two-part Charlie’s Angels episode—Angels in Vegas, featuring Dean Martin—were shot in the Tropicana’s casino, theater and pool area. And Martin’s friend Sammy Davis Jr. bought an 8% share of the property in 1972, making him the first Black person to own part of a Strip hotel.

Infamy also found the Tropicana. When mobster Frank Costello, a friend of Kastel’s, survived an assassination attempt in May 1957, police found the Tropicana’s gross win numbers in his jacket pocket. And an FBI investigation of the Tropicana in the late 1970s uncovered a Kansas City mob connection, a revelation that forced the sale of the property to the first of several corporate owners.

Over the years, numerous changes were made to the Tropicana to keep it competitive. Towers were added in the late 1970s and 1986. A 1980s remodel added a lush, five-acre pool area, with waterfalls, lagoons and swim-up blackjack tables, and tiki heads were placed around the property. For a time, the resort called itself “the Island of Las Vegas.”

“It was an interesting thing, seeing the Tropicana evolve to keep up with the times,” says UNLV professor and historian David Schwartz. “Their swim-up blackjack was a real innovation.”

The Tropicana’s last full remodel, to a South Beach theme, was completed in 2011. The results of that remodel are still visible at the Trop today, but they look as tired and faded as many of the older elements. Parts of the property still show life on a weekday evening—a few dozen diners are seated at Robert Irvine’s restaurant, and the Laugh Factory always draws a crowd—but they struggle to lift the mood of a property whose electronic marquee is currently thanking some 700 longtime employees who are about to lose their jobs. (In early March, Bally’s held a job fair with 20 local employers, striving to connect its soon-to-be displaced employees with new work.)

“I’ll really miss the people that work at the Tropicana. Some of them have been there since the ‘80s, the ‘90s,” Basil says. “I really liked the CEOs, the executives. They’ve been really good to us.”

Basil proudly notes that there’s been live comedy at the Tropicana since 1988, when Rodney Dangerfield opened his comedy club, Rodney’s Place, in the mezzanine space Laugh Factory now occupies. (Basil, who worked with Dangerfield on several of his movies, has multiple homages to the comic great weaved throughout the club. Respect.) Multiple comedy operators have occupied the space throughout the years, including an early iteration of Brad Garrett’s Comedy Club.Laugh Factory will survive the end of the Tropicana, Basil says; he’s in talks with several major resorts interested in becoming the club’s new home.

But while the 36-year reign of comedy at the Trop is impressive, it’s a distant second to the hotel’s biggest entertainment legacy: showgirl revue Les Folies Bergère, which ran at the Tropicana for nearly 50 years and never stopped being what Schwartz calls “a quintessentially Vegas show.” When it debuted on Christmas Eve 1959, it came on strong with a cast of 80 performers and a surfeit of rhinestones, feathers and flesh; a contemporaneous review in the Las Vegas Sun described it as “saucy, piquant and racy in the splendidly provocative French way.” Folies is arguably a large part of the reason Vegas is associated with showgirls even today.

Which brings us, full circle, to legacy. Thanks to the Nevada State Museum and guest curator Karan Feder, you can look at one of the show’s incredible showgirl costumes today. The east-west street that flanks the hotel to the north is Tropicana Avenue, and it will probably stay that way long after its namesake is gone. (Probably. Spare a thought for Riviera Boulevard, renamed for Elvis in 2016.) Amazingly, one of the tiki heads from the “Island of Las Vegas” phase, hand-carved by Ben “Benzart” Davis, was somehow saved from a remodel; it now sits at the entrance of local favorite Frankie’s Tiki Room.

The stained-glass ceiling of the Tropicana’s casino may also be saved, though exact details are unavailable as of this writing. Bally’s emailed the Weekly this official statement about the ceiling and the Tropicana’s other historic elements: “We are committed to safeguarding the rich heritage of our community and ensuring that future generations can experience the magic of our past. … Once finalized, we will share details on preserving the beautiful stained-glass ceiling over the casino floor.”

What is certain to survive the Tropicana is the myths, stories and legends we’ll perpetuate long after the hotel is nothing but museum pieces and memorabilia. The Stardust’s space-age sign and the Sands’ Copa Room still occupy people’s perceptions of Las Vegas, even though both have been gone for decades. We’re about to find out how big the Tropicana will loom in death. Perhaps the A’s might consider changing their name to the Las Vegas Islanders.