Circus Circus: Recalling the Strip’s wildest casino with monkeys, topless women

You’re no doubt familiar with Circus Circus.

Amusement park. Inexplicably good steakhouse. Giant neon clown out front.

It’s been a family favorite for the past 48 years.

The thing is, though, Circus Circus will have been open for 54 years next month, and those first five-plus years are the stuff of legend. Shocking, head-scratching, rarely-talked-about legend.

The early days when colorful Caesars Palace developer Jay Sarno was in charge were so wild that the fact that mobster and “Casino” inspiration Anthony Spilotro operated the Circus Circus gift shop barely cracks the top 10.

Back then, the casino floor was home to trained monkeys, the occasional live bear sitting at a blackjack table and a craps-shooting, slot-playing elephant named Tanya.

Traditional midway attractions such as Skee-Ball competed for attention with a peep show and a nearby baseball toss where the prize was having a topless woman dance for you.

Among the entertainment options were the shows “Nudes in the Night,” “Nudes Delight,” “Naked But Nice” and “Hot Pants Sexplosion.”

All while Circus Circus was being positioned as a place for families.

In retrospect, Sarno’s business plan wasn’t that far removed from, “Fellas, we’re going to build a $15 million circus tent, encourage gamblers to bring their young children, cram it full of as many carnival games and topless ladies as regulators will allow and, you know, just see what happens.”

‘Almost a parody’

In previewing his latest creation, Sarno described what to expect once Circus Circus opened on Oct. 18, 1968.

It read like a descent into madness.

“The customer will be confronted with jugglers, fortune tellers, trapeze and high-wire acts operating right over the gambling area. We have signed the finest circus acts in the world.”

So far, so good.

“As you go from the second floor to the first floor in this particular establishment, you can use a slide, a fireman’s pole or a ramp surrounding a stage with all kinds of entertainment: trampoline, unicyclists, more jugglers, a weight guesser, a fellow spinning dishes and catching them before they fall.”

A slide? And a fireman’s pole?

“Then, all of a sudden, here comes a Highland Marching Band. There’s a girl selling balloons. Over there is a very provocatively dressed shoeshine girl.”

Why was there a “very provocatively dressed shoeshine girl” in a venue designed for families? That’s easy. It’s because the Nevada Gaming Commission vetoed Sarno’s plans for the shoeshine girls to be topless — as well as his desire for topless trapeze artists.

“Here’s a fellow leading two little pink elephants, you can ride them or pet them,” Sarno continued. “You can play a slot machine with our Money Monkey, who jumps for joy if you win or holds his head in sorrow if you lose. There’s another monkey who runs a store. If you want something, give him the money, and he’ll bring you the product.”

A monkey.

Who runs a store.

“In certain ways,” UNLV historian Michael Green says, “it was almost a parody of what people thought Las Vegas was about.”

The scene was surreal enough to send no less an authority on debauchery than writer Hunter S. Thompson — and/or Raoul Duke, his “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” stand-in — scurrying to saner pastures.

Granted, Thompson/Duke was high on both mescaline and ether at the time, but still.

Early signs of trouble

So much of Sarno’s plan sounds like a pubescent fever dream, but coming off the grand success of the Caesars Palace opening just two years before, there was little reason to doubt the former Miami tile contractor.

“He definitely was larger than life,” says David G. Schwartz, another UNLV historian and author of “Grandissimo: The First Emperor of Las Vegas,” which details Sarno’s rise and fall. “He was a big man with pretty big appetites and figured that other people had those same appetites and would want to indulge them in Vegas.”

Circus Circus was far from a one-man show, but Sarno’s ideas were the grandest, and his voice was the loudest.

Problems arose almost from the beginning.

Serious gamblers didn’t appreciate the many distractions that, in addition to the live animals, included the likes of the Flying Cavarettas soaring overhead.

Other whimsical touches also missed their mark.

“If you have grown accustomed by that time to the idea of wearing your jacket and tie or dressing nicely for an evening, which the casinos certainly encouraged in those days, sliding down a fireman’s pole is probably not for you,” Green allows.

The slide presented similar obstacles for the well-heeled guests.

While covering opening night, Ann Valder, the Review-Journal’s assistant women’s editor — yes, we had one of those — reported, “Climax of the evening for me was a ride on the slide from the main floor to the pit which left me shaking for 10 minutes.”

Another concern? Sarno and his team were so short on cash, Circus Circus operated without a hotel until the summer of 1972, and the casino charged as much as $2 just to get inside.

“I really do think the admission charge was a problem,” Green says, “and I base that partly on the uproar here just in the last few years about paying for parking on the Strip. I think that was kind of a deal killer for a lot of people.”

Especially considering the cost of a gourmet dinner, including wine, at the casino’s Cafe Metropole was just $2.50.

Family appeal?

“We have built a project that’s suitable for the entire family,” Sarno announced ahead of the opening. “There’s a huge nursery complex for children — and yet we have a swinging place for adults as well.”

Circus Circus wasn’t the first casino to accommodate children. The Hacienda, where Mandalay Bay now stands, added a miniature golf course and a go-kart track. The Last Frontier Village, a Western theme park with bumper cars and other attractions, preceded Sarno’s creation by two decades.

This, though, was the first casino intended to appeal to children and families, with the youth expected to remain on the second floor with the various carnival games while their parents gambled in full view below.

Sarno is often compared to P.T. Barnum, with the circus motif really driving that point home. But there was quite a bit of Willy Wonka in him, as well — in that he also created a world designed to entice children that was in no way suitable for them.

“OK, you have kiddie attractions and nudity. … That is a contradiction that doesn’t work too well, then or now,” Green notes.

The International, currently known as the Westgate, opened a year after Circus Circus with an area dedicated to children.

“They set things up for kids to do, and they were quite separate from going to the lounge to, say, hear Redd Foxx do a monologue,” Green recalls. “Circus Circus didn’t really have that strong a separation, and that’s a problem.”

Regulators push back

The half-naked shoeshine girls and trapeze artists were a no-go — “LV Circus Casino Approved; No Topless Shoeshine Girls,” a Review-Journal headline blared — but regulators apparently had fewer qualms about an actual peep show mixed in among the family attractions.

“For only a quarter, you can see the most beautiful and exciting girls in the world,” we wrote in a preview. “Just like in the old Arcade, buddy, but the world’s most beautiful girls, in the flesh.”

Another attraction let players toss baseballs — three for a quarter — at a target, kind of like a dunk tank. As Sports Illustrated described the game at the time, there were “two white fur-covered beds, on which recline two topless 6-foot girls who fall off and do the frug” — relax, kids, it was a dance craze — “if someone hits a small circular target from 30 feet away.”

Sarno brought in Dodgers pitching legend Don Drysdale, who earlier that year had set a major league record by tossing 58 consecutive scoreless innings, to christen the attraction. He missed all three throws.

So did Marty Allen. The comic, who was performing at the Riviera, took things a bit further after his misses by hopping over the counter and pushing the target with his hand.

Less than a week after it opened, the gaming commission said it wanted that particular concession “completely screened off.”

Screened off, but not closed.

Girls, girls, girls

“Already the traffic of beauty into our offices is unprecedented” Sarno said shortly before the grand opening. “The girls have heard about us and our attractive costuming program, and they are beating a path to the doors of Circus Circus.”

Keep in mind, the National Organization for Women had been around for 2½ years by this point.

“We also are going to have the most beautiful girls in the world catering to our customers in 14 bars and varied eateries at Circus Circus,” Sarno continued.

That included Cafe Metropole, which we described as offering a gourmet dinner with “slave girls to serve your every need.”

There was a “monorail of beauty” in which “a score of beautiful women encircle the gaming-entertainment palace in a small, intricately decorated train.”

The Cage Girls, go-go dancers who performed behind bars while traveling along an aerial track, were introduced by the casino’s ringmaster: “And now our dazzling display of devastating epidermis!”

Most shockingly, Schwartz says the ticket booth was set up to activate air jets that would lift customers’ skirts.

It’s honestly surprising that stunt didn’t land somebody in jail.

That’s entertainment

When it comes to entertainment, you’re not going to top a show called “Hot Pants Sexplosion.”

You just aren’t.

No matter its content nor its reception, once you present a show with that title on a marquee, you’d might as well find a new line of work, because you’ve reached the pinnacle.

Presented in six installments from midnight to 7 a.m., presumably to satisfy the city’s breakfast-hour “hot pants” needs, the show was one of several attempts at entertainment before executives ceded that to the circus acts.

The Hues Corporation, the pop/soul trio of “Rock the Boat” fame, got its break playing the lounge during that era.

In 1970, Sarno brought in a stage version of “Tom Jones,” an update of the Oscar-winning comedy. In keeping with the house tradition, it, too, was presented topless.

As for those circus acts, Sarno sought out some of the best in the world, many of whom were thrilled to get off the road, settle down and raise a family here.

There was Steve McPeak, who rode his unicycle to Las Vegas from Chicago, wearing out two pairs of shoes, three tires and five pairs of pants along the journey.

Twins Billy and Benny McCrary tipped the scales at a combined weight of 1,300 pounds.

The act known as Cuneo’s Nine Siberian Tigers was truly something. Here’s our description of what transpired: “In another feat, one of the tigers, Volga, rides on a horse, a natural enemy of the tiger, with (trainer Josip) Marcan sitting on top of the tiger.”

First off, the horse is a natural enemy of the tiger? And Marcan was said to have been the only person to have accomplished that particular feat, but how many people could have possibly tried and failed to ride a tiger while it was riding a horse?

At times, the animals intersected with the burlesque. In 1969, the Klauser Bear Act joined “Nudes in the Night.” The following year, Tanya the elephant was added to the cast.

Everything to excess

Whether it was women, food or spectacle, Sarno seemingly never encountered the words “too much.”

Circus Circus opened with the “Diet Buster,” an all-you-can-eat-for-a-dollar dessert extravaganza featuring ice cream sundaes, cakes, pies, doughnuts, coffee, tea and milk — along with a separate concession offering all the doughnuts you could eat for 50 cents. In the Bavarian Beer Fest, guests could drink as much beer and make as many sandwiches as they wanted, all for $1.

For every dollar spent on one of the 20 carnival games, Sarno promised players would receive two dollars worth of merchandise. Prizes included color television sets, golf clubs and fur coats. If you won one, you could buy more at cost.

Sarno was wild about those furs. He recruited New York furrier Nathan Haber to open the casino’s Fur Menagerie, which was stocked with more than $250,000 worth of inventory. Fur auctions took place at 2 a.m. each Sunday.

As one of the prizes during the $300,000 Jumbo Jackpot Jamboree, Sarno touted “a real life African bull elephant with ivory tusks valued at $62,000 by Lloyd’s of London.”

“Maybe part of the problem,” Green suggests, “was that everything was designed to be so attention-getting, exciting, outrageous. It was hard to get a break.”

With no hotel rooms to serve as a retreat during the early years, the only way guests could get that break was to leave the property.

Circus Circus reined in

Things calmed down over time, mostly once Sarno stepped away.

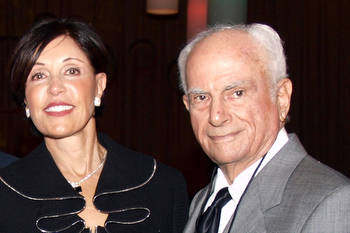

In 1974, while he and his business partner and college roommate Stanley Mallin were under a federal indictment for trying to bribe an IRS official, charges they were cleared of the following year, Sarno leased all operations to William Bennett and William Pennington. The duo bought the casino outright in 1983.

Green cites “the old story that Bennett walked in, pointed at the lounge and turned to Mel Larson” — Bennett’s business associate with whom he’d later help open Las Vegas Motor Speedway — “and said, ‘That’s a buffet by Monday.’ They saw that Circus Circus was designed in a way that wasn’t going to work.”

Most of the shenanigans were relegated to history, and the circus acts that continue to this day were relocated. A new approach, providing inexpensive meals and rooms for middle-class visitors, quickly came into focus.

“Maybe they didn’t gamble so much individually,” Schwartz says of the new clientele, “but there was a lot more of them. It’s been a winning model.”

Sarno’s legacy

In many ways, Circus Circus was ahead of its time — although there’s never really a good time for blowing random women’s skirts into the air.

“Themed resorts? Most people would give Sarno the credit,” Green says.

Circus Circus Enterprises, Bennett and Pennington’s company, also developed Excalibur and Luxor before it was swallowed up by what would become MGM Resorts International.

Both resorts, as well as fellow Circus Circus Enterprises property Mandalay Bay, had dedicated areas and attractions for children, as they came online in the 1990s during Las Vegas’ push as a family destination.

Before Sarno, the now ubiquitous slot machines were an afterthought — a few of them scattered here and there, out of the way, to entertain the ladies while the gentlemen did the real gambling. Circus Circus opened with 700 of them.

With his passion for themed hotels and water features — fountains were a focal point at both Caesars Palace and Circus Circus — Sarno was a major influence on Steve Wynn, who revolutionized the Strip in 1989 with the opening of The Mirage.

Ask Schwartz about Sarno’s legacy, and the author doesn’t hesitate.

“I think he should be remembered as one of, if not the, greatest visionary in Vegas history,” Schwartz says. “He really did change where the city was going.”

One unbelievable step at a time.

clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.

.jpg)