Mets’ casino gamble could crap out in parking lot

EDITORS’ NOTE: The location of CitiField, home of the Nets, was solicited by Robert Moses, the architect famous for car-centric urban development and design around the New York metropolitan area and contiguous states. Since the last midcentury and post-war fruition of personal automobiles – quintessential to the suburban lifestyle – the Queens neighborhood of Willets Point (as well as all Long Island) has evolved, sculpted by population influxes, exoduses and a new urban class. Yet, the utilization of urban spaces for activities like gambling evokes the question of whether those casinos, which may bring in crucial tax revenue for the city government, are in the right place at all. Better here, around Queens-Brooklyn working families, or in Atlantic City, maybe Las Vegas? Other sites for the potential construction of casinos, as well as licenses for casinos, have been discussed or given out: sites-of-interest include Manhattan’s Times Square and Hudson Yards.

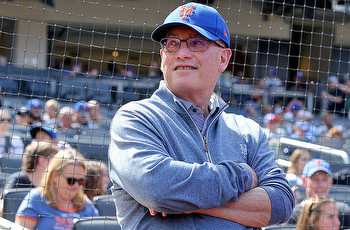

The owner of the Mets has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars lobbying city officials in connection with his push to build a casino near Citi Field — but there could be multiple legal hurdles to bring the slots to Queens.

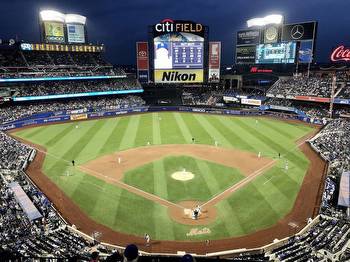

Both state law and the team’s own lease agreement with the city stand in the way, in particular a financing deal tied to the parking spaces, and rules about building on park land.

Owner Steve Cohen’s dream of turning Willets Point into a gambling hub materialized earlier this year when Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed creating three more downstate casino operator licenses.

As far back as January, Cohen was pitching the idea of a casino around his ballpark to local and state elected officials, THE CITY previously reported. Other real estate developers are eyeing casinos for Times Square and Hudson Yards in Manhattan, and Coney Island in Brooklyn, according to reports.

The plan for Citi Field includes possibly erecting a casino on a stadium parking lot, or across the street at Willets Point, people familiar with Cohen’s proposal told THE CITY.

But building on any of the parking lots would require state legislators to override a legal principle known as the public trust doctrine, which prohibits private development on public land.

The Mets’ original playground, Shea Stadium, was built in the 1960s following Albany deals that allowed construction inside what is technically Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, owned by the city Department of Parks and Recreation.

An attempt from the team’s previous owners to build a mall on the Citi Field parking lot was struck down by the State Court of Appeals in 2017 for public trust doctrine reasons. Later that same year, the city itself had to get state approval to build a pre-K next to the New York Hall of Science in the park.

Lots of problems

On top of the public trust issue, any construction project that takes away parking spots from Citi Field would complicate the team’s repayment of hundreds of millions of dollars in municipal bonds it has through the city, which are partially tied to revenue from parking.

People familiar with the financing and the deal to build the stadium said any removal of parking spaces would require significant changes to the organization’s financing deal with the city. And the organization would have to find ways to make up the lost parking, likely through multi-level parking decks — which could further complicate any construction project.

The team and Citi Field’s official owner, Queens Ballpark Company LLC, leases the land from the city. Stadium construction was paid for in part by municipal bonds issued through the NYC Industrial Development Agency, a division of the city’s Economic Development Corporation.

In the deal hammered out by former owner Fred Wilpon in 2006, QBC agreed to maintain more than a dozen parking lots in and around the stadium in connection with its approximately $650 million bond financing, according to officials with the EDC and documents reviewed by THE CITY.

The lots include those spaces around the stadium as well as ancillary parking lots inside Flushing Meadows-Corona Park that are used for railroad commuters and for other events, including the U.S. Open, according to the financing deal.

A 2017 audit by then-comptroller Scott Stringer found the Wilpon family had underreported the amount of the previous year’s revenue from managing parking lots by nearly $300,000, out of about $8 million total.

The audit explained that the organization pays its base rent to the city based on a formula that calculates whether net revenue from parking and non-parking operations — like special events — exceeded predetermined amounts of money, according to the audit.

Queens Ballpark Company refinanced those bonds last year, soon after Cohen finalized his purchase of the Mets for $2.4 billion in Nov. 2020.

A spokesperson for Cohen said he’s still considering all options for what to do around Citi Field.

“Steve views owning the Mets as a civic responsibility, and has made investments in the team, the ballpark and the community his number one priority,” Tiffany Galvin-Cohen, who is not related to the Mets owner, told THE CITY in a statement.

“Steve is continuing to engage and listen to stakeholders. Any strategic vision for the area will aim to help revitalize the neighborhood and improve the experience for Mets fans,” she added.

Galvin-Cohen did not directly respond to questions about the parking revenue’s use in paying off the municipal bonds. A spokesperson for the EDC, which oversees the IDA, declined to comment on the story.

One person familiar with the original deal noted that it could be possible to get around the lot space problem by building stacked-level parking.

Pay to play

As the team sought refinancing of the municipal bonds in January of 2021, representatives from Cohen’s Stamford, Conn.-based financial firm Point72 launched a limited-liability company in Delaware called New Green Willets, records show. That organization then began lobbying New York officials about a casino plan.

New Green Willets has paid $120,000 so far this year to Moonshot Strategies and Hollis Public Affairs to press city officials on Willets development, including a potential casino, lobbying records show. New Green Willets itself has also spent more than $98,000 lobbying City Hall and other elected officials pertaining to development in and around Willets Point — on everything from creating hiking trails along Flushing Creek to building more housing, along with the casino.

The 23-acre public-owned portion of Willets Point, which has been filled with moon crater-sized potholes auto-body shops for decades, is currently undergoing an “environmental remediation” overseen by the state Department of Environmental Conservation, which is cleaning up the area ahead of a sweeping redevelopment project.

The current plan is to build 1,100 units of affordable housing, new businesses, hotels and a new public school by the end of the decade.

There are also nearly 40 acres of privately-owned land around Willets Point, but Cohen would have to buy that land out — and likely require more years-long environmental remediation before construction could even begin, experts said.

“Even if Steve Cohen succeeded in getting state alienation, and a casino license, the Mets will still need to comply with their lease agreements regarding the number of parking spots,” said a person familiar with the lease agreement.

“It’s not so easy to just say you want to build a casino in a city parking lot.”