Impacts On Poor Cited As Gambling Expansion Continues

BOSTON (State House News Service) - With Massachusetts in the early days of its most significant expansion of gambling in a decade, a researcher from the United Kingdom shared his perspective on how gambling worked its way from the shadows of society to the mainstream, and the implications that has had in Britain.

The Public Health Advocacy Institute at Northeastern University School of Law hosted a webinar Wednesday afternoon that focused on "how the gambling industry misleads regulators and imperils the public's health." It featured executive director Mark Gottlieb, anti-tobacco litigator Richard Daynard, gambling researchers from the UK, and Harry Levant, a gambling addict in recovery.

Jim Orford, emeritus professor of clinical and community psychology at the University of Birmingham and an author on gambling harms, said that gambling is something of a reverse Robin Hood.

"We know that gambling contributes to inequality because in terms of percent of income, percent of wealth, that is lost to gambling, the relatively poor are contributing more than the relatively rich," he said. "So in a way, gambling has become something that is being taken from the poor and given to the rich."

Orford told attendees that the only legal betting available when he was a "youngster" was on horse races, and bets could only be placed at a track or with a "booker's runny" in a backroom or back alley. Then, in the 1960s, betting "shops" or "offices" were allowed so bettors didn't have to travel to the track itself. The National Lottery was created in the 1990s and the 2005 Gambling Act "essentially normalized gambling as a commercial activity," he said.

"So what we've now got is a total transformation of the place of gambling in society. It's now not just tolerated as it was in the 1970s, 1980s, even in the 1990s, it was considered something that, yes, people did and it should be tolerated but it shouldn't be encouraged," Orford said. "And this was a complete transformation in my lifetime. It is extraordinary, I just wanted to get across to you just how extraordinary that has been."

Orford added, "And Britain, I know, is an exception in some ways. I mean, we have rather lead the way, I'm sorry to say, in gambling. But I know much the same has been happening in the United States."

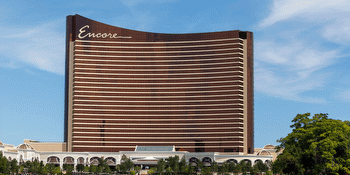

Once mostly confined to destinations like Las Vegas or Atlantic City, commercial gambling has taken off across the United States in recent decades. Massachusetts legalized casino-style gaming in 2011, with then-House Speaker Robert DeLeo playing a major role in the expansion of gambling. DeLeo now works as a "university fellow for public life" at Northeastern University, whose law school hosted Wednesday's gambling harms event.

There were 981 tribal or commercial casinos across 44 American states at the end of 2022, according to the American Gaming Association, including three in Massachusetts.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in May 2018 that states were free to legalize sports betting, 36 states have done so and 33 are taking bets, the AGA said.

And in turn, state governments have become increasingly accustomed to the revenue that is generated from gambling activity including in Massachusetts.

The first full month of in-person sports betting here generated more than $25 million in wagers, more than $2 million in revenue for sportsbooks and just more than $300,000 in taxes for the state, the Gaming Commission said Wednesday.

Plainridge Park Casino, MGM Springfield and Encore Boston Harbor took more than $25.7 million in wagers last month and kept $2.01 million as revenue after paying out winnings and federal excise taxes. Encore led the way with a monthly handle of $16.9 million and taxable revenue of just more than $857,000. Plainridge had a February handle of just more than $7 million and reported just more than $890,000 in monthly revenue. MGM Springfield took $1.76 million in wagers and generated about $262,000 in monthly taxable revenue.

Revenue from in-person sports betting is taxed at 15 percent, and the state's take for the month came to $301,533.52, the Gaming Commission said. That state revenue is split into various buckets: 45 percent to the General Fund, 27.5 percent to the Gaming Local Aid Fund, 17.5 percent to the Workforce Investment Trust Fund, 9 percent to the Public Health Trust Fund, and 1 percent to the Youth Development and Achievement Fund.

In-person betting began Jan. 31, so the release Wednesday of February gambling revenues provides the first real picture of the money generated by the newly legal activity.

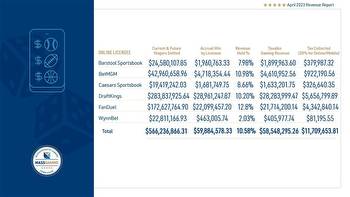

Mobile betting began March 10 and revenue generated from it will first be reported by the Gaming Commission in mid-April. GeoComply, a company that provides geolocation and fraud detection services, said that it recorded 406,437 unique player accounts and 8.1 million "geolocation transactions" last weekend across the six mobile operators that went live in the Bay State on Friday.

The company said it also prevented more than 5,000 transactions from "devices or accounts with a known history of fraud, saving its customers tens of thousands of dollars."

Revenue and state taxes from casino-style gambling, which has been available here since 2015, was far more significant in February. The three casinos together reported more than $98 million in slots and table games revenue, which worked out to a state tax hit of about $27.4 million, the commission said.

Encore counted $62.7 million in revenue last month, $29.9 million from its table games and $32.8 million from its slot machines. The Everett casino's monthly tax bill totaled almost $15.7 million. MGM's $23.26 million in February revenue came mostly from slots ($17.86 million versus $5.4 million from table games), and the casino owed the state more than $5.8 million for the month. Plainridge Park's slots generated just more than $12 million in revenue, which in turn resulted in $5.9 million for the state.

Encore and MGM are each taxed at a rate of 25 percent of gross gaming revenue and the money collected is split into buckets, like local aid, the Transportation Infrastructure Fund, and an education fund. Plainridge Park pays a 49 percent tax on its gross gaming revenue, with 82 percent of what is collected earmarked for local aid and the remaining 18 percent allotted to the state's Race Horse Development Fund.

The Mass. Lottery reported $590.5 million in sales in January, the most recent month for which data is available. The Lottery kept $120.8 million of that as its monthly profit. The Lottery's profit is returned to the state to be used as general government aid to the state's 351 cities and towns.

The Lottery has regularly produced $1 billion a year for the state to use as local aid (and more than $31 billion across its 50-year history), and Lottery overseers continue to push for the authority to offer games online, which they say will help the agency compete in the changing market.

Since Plainridge opened in June 2015, Massachusetts has collected $1.344 billion from casino-style gambling.