How pinball machines helped pave the way for gambling in South Dakota: Looking back

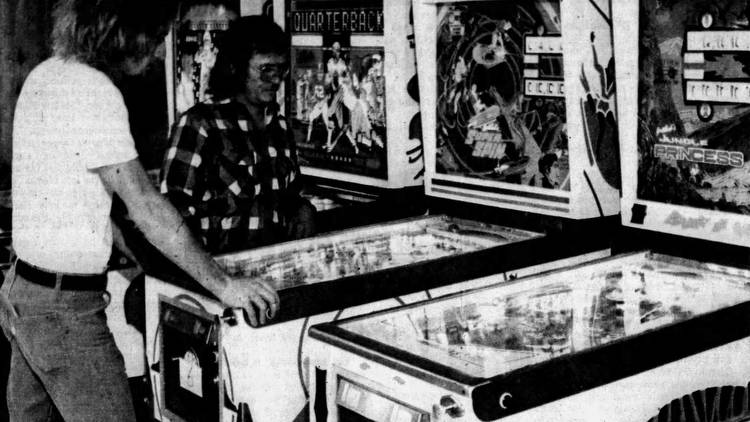

If you’ve ever been in a good arcade, you’ve been inundated by the sounds of electronic boops, beeps and pew-pews. One of the most recognizable sounds you’d hear were the sounds of pinball machines. The thump of the flippers, the chimes of the bumpers, the roll of the ball, and the excited ding of the score as it climbs. You may remember old pinball machines with vague, generic themes, or maybe branded themes like Elvis, Batman, the Addams Family, or many more. Pinball machines weren’t always the stuff of family amusement venues like Granny’s, Gigglebees, or Land of Oz. There was a time where they were more apt to be spotted in bars, taverns, and saloons.

The pinball machine had its origins in lawn-based ball games like bocce or croquet. These games went on to inspire indoor games like billiards and pinball. The original pinball games involved a board studded with pins, which acted as obstacles and pockets. Each pocket had a score, and the more difficult pockets to land in would have higher values. Not surprisingly, these became gambling machines. Sometimes, they could award coins on their own. Sometimes, a proprietor would verify a score and award the money.

Games of chance like slot machines and pinball machines were found in Sioux Falls as early as the 1930s. They were likely here earlier, but not labeled as vice until later. In December of 1937, pinball machines were in the sights of State’s Attorney E. D. Barron, as he ordered all such devices removed under the threat of stiff financial penalty and jail time. State law said, in more legal terms than these: Any machine which money is paid into, at the chance of receiving merchandise, money, or articles of value, is a gambling machine. The early pinball machines were not games of skill, as they had no mechanism incorporated to control the ball after it was launched onto the field.

Despite the law of the state, in 1939, Huron decided to license the machines. Those who wanted to install them would have to pay the city to do so. Other cities followed suit thereafter, even though the licensing equated to a tacit acceptance of the machines, which were considered gambling machines by the state.

Over time, pinball machines were changed to overcome the complaints against them. To the objections about the devices being games of chance, manufacturer Gottlieb introduced the flipper, which, placed in pairs at three spots in the machine, offered the player more control over the ball’s journey. To answer the objections that the machines were for gambling, payouts were eliminated, but free games became available electronically.

In 1948, just days after police raids in Sioux Falls confiscated and destroyed 16 slot and pinball machines, Attorney General Sigurd Anderson opined that even if a pinball machine paid no prizes and could be played for free, it could still be used for side bets, and therefore subject to confiscation as a gambling machine. He, seemingly obsessed with eradication of pinball machines, conveniently ignored the fact that any event or outcome could be bet on in the same way.

By the late 1960s, the fervor against pinball machines ebbed, and most cities began to drop their bans against the game. In 1976, pinball aficionado Roger Sharpe was called before the New York City Council to prove that the amusement was a game of skill. He moved the ball around the field with skill and mastery, convincing the powers that be that it was indeed a game of skill.

South Dakota changed its mind on April 23, 1970 when state Attorney General Gordon Mydland stated, finally, that a free or extended play was not “a thing of value, but is merely doing a useless thing free”. Other cities were even later adopters of this wisdom; Oakland, California finally eased its ban in 2014.

Today there are several local businesses that offer pinball to customers. This game, ever-evolving and timeless, continues to fascinate arcade goers with its flashing lights and ringing bells.