Games of risk: Gambling laws look to shut out loot boxes

The Karnataka Legislature recently introduced amendments to the Karnataka Police Act, 1963, under the Karnataka Police (Amendment) Bill, 2021. The state sought to prohibit online gambling, namely online games. One of the objects of the amendment is to “curb the menace of gaming through the internet, mobile app”.

This led to significant doubts both in the Assembly and among the public whether the state sought to prohibit online gaming in its entirety. However, the amendments targeted only online games that involved games of chance and payment of real money that resulted in uncertain dividends, i.e., gambling.

Online games or video games that have no element of chance based on the payment of real money are not covered under the ambit of the proposed legislation. Although the amendment directly affects various online portals that offer online casinos and other traditional gambling-based card games in an online avatar, here we are analysing the impact of the amendment on a specific area — loot boxes in online games.

Loot boxes can be simply defined as in-game purchases (with real money) where the players do not know what is in a box until they have bought it. This virtual ‘box’ is akin to a sealed treasure chest full of highly desirable goodies that the player purchases without knowing its contents. The purchase is a gamble regarding the contents of the boxes. It could sometimes contain highly desirable virtual commodities such as virtual weapons, armour or other perks that can be used in the game to ensure victory. Most of the time, however, the loot boxes contain nothing, and the player would have lost real money.

The practice of offering loot boxes can be traced to 2004 with the prevalence of ‘free-to-play’ games that required players to invest real money to purchase desirable or sometimes necessary items. This practice thereafter expanded to games that consumers purchased at full prices so that the developers could turn a bigger profit. Major developers such as EA, Blizzard and Activision have defended loot boxes at various points in time. Loot boxes are presented in an ornate graphical design that animate vividly when purchased and open in a great reveal after the consumer has paid for them. Most game developers also made purchasing such loot boxes incredibly easy by pre-linking credit cards at the time of installation of the game. The trend caught on very quickly and major games such as ‘Fortnite’, ‘PUBG’ and ‘Call of Duty’ also started offering loot boxes in various forms till 2019. Most children who play these games would lose significant amounts of money online with the hope of securing better virtual weapons, virtual attire, etc.

In 2020, the UK’s National Health Service mental health director Claire Murdoch said that loot boxes are “setting kids up for addiction by teaching them to gamble”. Loot boxes have drawn similar condemnation from many other countries in the EU, the US and Australia. Additionally, since gaming is a large industry with its own e-sport arena, professional e-gamers and consumers also started to protest these practices. In response to overwhelming protests and strict regulations across the world, many major developers stopped offering loot boxes. Fortnite, PUBG and Call of Duty do not offer loot boxes as before, whereas Counter Strike permits players to preview the content of loot boxes prior to purchase. However, some games (both mobile and console/PC) continue to offer loot boxes in exchange for real money. Consequently, gamers continue to gamble away real money in exchange for virtual perks.

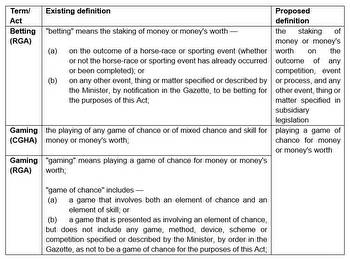

The definition of ‘gambling’ and ‘online gaming’ in the proposed amendment to the Police Act applies squarely to loot boxes. ‘Gaming’ has been defined to mean and include online games, involving all forms of wagering or betting, including in the form of tokens valued in terms of money paid before or after issue of it, or electronic means and virtual currency, electronic transfer of funds in connection with any game of chance. An explanation is inserted where any act of risking money, or otherwise on the unknown result of an event, including on a game of skill shall also fall within the prohibition under the amendment. Notably, game developers are also included vide an amendment to the definition of ‘place’ under the Act. The term ‘place’ will also include cyberspace and virtual platforms under its ambit, thereby penalising game developers who offer loot boxes under S.78 of the Police Act. The developers will therefore fall under the definition of persons offering a ‘gaming house’ under the Act and will be liable for strict penalties that may include imprisonment for up to three years and fines up to Rs 1 lakh.

Further, the amendment also penalises participants and gamers with less stringent penalties in contrast to the developers. This part of the amendment would mean that all persons who purchase loot boxes in Karnataka would also be liable to punishment with imprisonment for a period ranging between six months and 18 months and fines ranging between Rs 10,000 and Rs 20,000.

Loot boxes are often offered in an extremely cloaked and nuanced manner. The investigation will therefore require sophistication and expertise from the investigating agencies.

These games and loot boxes are often offered by developers and persons who do not operate within the territory of India. Investigation and punishments of offenders under the amendment will require significant resources of the agencies to trace the developers and the players.

Thereafter, the state government will also require the support of the Union if it seeks to block games/apps under S.69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000. These challenges are apart from the challenges faced by the judicial system in deciding trials under special laws.

The promulgation of the amendment is a promising start and will benefit consumers if the amendments are implemented in letter and spirit. In view of the mass consumer appeal of video games, appropriate regulations to prevent developer greed are most welcome.

(The writer is an advocate practising in the Karnataka High Court)