‘Dark business’: Thailand braces for World Cup gambling frenzy

Bangkok, Thailand – Every 15 minutes, a small crowd gathers at a shack in a Bangkok market to wait for the numbers to be drawn.

The buzz of anticipation at each ping-pong lotto draw is palpable but the excitement is invariably short-lived.

When the number five is called out at a recent draw, a man chewing a betel nut sighs at his loss of 1,000 Thai baht ($28). Another scrunches up the paper containing his 20-baht ($0.50) wager.

Punters who guess the right number can win 10 times their stake. But in the end, the house always wins.

“We can make up to $15,000 a month from each table and we can pay the right people to stay open,” the streetside bookmaker operating the draw told Al Jazeera, asking to remain anonymous.

With the Qatar World Cup kicking off on Sunday, Thailand is bracing for a surge in gambling, which, despite being wildly popular, is illegal outside of a handful of state-approved venues.

While Thailand did not qualify for the tournament, Thais are expected to wager up to $1.6bn on the games, according to researchers at the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce.

“World Cup fever will spur a 50-percent increase in gambling newcomers,” Thanakorn Komkris, the secretary of the Stop Gambling Foundation, told Al Jazeera.

“But what’s sad is that about one-quarter of those newcomers will turn into regular gamblers based on our experience with past football tournaments.”

Under Thailand’s 1935 gambling law, betting is illegal outside of the official lottery and a small number of horse racing tracks.

Authorities have long argued that gambling runs against the principles of Buddhism, Thailand’s majority religion, and encourages other social ills to flourish.

Still, illegal casinos, online betting shops, underground lotteries and pop-up bookies taking bets on everything from cockfighting to Muay Thai are pervasive, forming a shadow economy worth billions of dollars a year.

The COVID-19 pandemic and technology have made gambling easier than ever, said Thanakorn, the anti-gambling activist, with people short of cash turning to illegal websites that have sprung up across the Southeast Asian country.

“More than one million Thais identify as pathological gamblers,” he said.

“Some fall out with families because they have to borrow money, but many others turn to loan sharks who are often tied to illegal football websites … they are entwined like a web.”

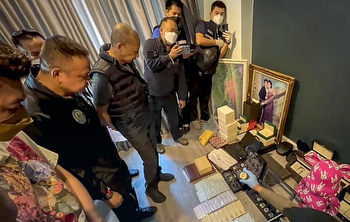

Ahead of the World Cup, Thai police said last week they had closed down 500 websites linked to a nationwide gambling syndicate known as “Fat Fast.” Authorities seized nearly $13m in assets as part of the raids, local media reported.

Jun, a 34-year-old office worker in Bangkok, knows first-hand the temptations that accompany World Cup fever.

He lost about 40,000 baht ($1,120) – several times an average month’s salary – during the 2018 World Cup in Russia, during which he wagered up to 2,000 baht ($55.70) on each match. Despite his losses, Jun plans to have a flutter this time around as well.

“But with the unstable economy I don’t think I can risk that much this time,” he said. “I just want to take part, it makes watching the games so much more interesting.”

Like many Thais, Jun places his bets with neighbourhood motorcycle taxi drivers, who act as streetside agents for the underground bookies that ply their trade in almost every community.

But he says the real money is to be won – and lost – online, where millions of baht can be at stake.

Many of those companies are based along the Thai border with Cambodia, according to authorities.

The Center for Gambling Studies at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University has estimated that these gambling sites have created up to 700,000 new gamblers this year alone.

The Thai money moving through these websites – as well as the proliferation of casinos in neighbouring Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar – has led some legislators to float the idea of amending the 1935 Gambling Act to allow licensed casinos.

In June, parliament heard a debate on the issue, which led to the establishment of a committee to assess an easing of the law. If successful, the push to bring gambling out of the shadows would break longstanding taboos and potentially bring in billions of dollars in tax revenues currently flowing into illicit businesses.

Opponents argue that the businesses that win the licenses to operate will inevitably grow so big, so fast that authorities will struggle to rein them in, especially if they are accompanied by illicit activities such as prostitution, human trafficking, drugs and money-lending.

Activists such as Thanakorn have also argued any legal changes must be preceded by a robust debate about the health and social consequences in a nation already obsessed with betting.

“There’s no way this is a good idea,” Thutchakrit Wongpanaporn, an ex-gambler who runs a YouTube channel dedicated to warning people of the dangers of gambling addiction, told Al Jazeera.

“Unless Thailand can regulate gambling like other Western countries, I just don’t see it,” said Wongpanaporn, popularly known as Sia Joe, who lost more than $1.5m to his addiction. “The government has to control online gambling first before thinking about legalisation of casinos.”

There are also fears about who would take control of the gambling business, with casinos in neighbouring Cambodia and Laos gaining a notorious reputation as hotbeds for online scams run by Chinese criminal gangs.

“In a ‘dark business’ like gambling, which has ties to criminal activities, there is no regulator strong or serious enough to handle it,” Wongpanaporn said.

To gamblers like Jun, though, legalisation could only be a good thing. Whatever its drawbacks, it would at least free millions of Thais from the threat of legal sanction.

“The thing is in Thailand, gambling is part of our DNA,” he said.