Casinos broke their promise to Illinois

This was an act of self-interest. But that wasn’t the language Weidner used.

Instead, he argued that any such casino would run contrary to the intent of the Illinois legislature, which had justified its approval of gambling in Illinois by arguing that these new riverboats would revive the downtowns of communities that were demonstrably struggling with deindustrialization and other economic shifts.

The riverboats were supposed to bring people back to these downtowns and, Weidner argued, if Chicago was allowed to big-foot the whole enterprise, the revitalization of these former industrial cities would either be halted or diminished.

Weidner and his group prevailed. When the two-boat Hollywood Casino opened in Aurora in 1993, the pavilion from where the “cruises” commenced featured a gorgeous steakhouse and an epic, Vegas-style buffet ― not to mention gleaming display cases showcasing Douglas Fairbanks Sr.’s “Zorro” cape, a Charlie Chaplin bowler and Charlton Heston’s Roman toga from “Ben Hur.” At the Paramount Arts Center across the street, the casino booked (and subsidized) Las Vegas-style performances by Liza Minnelli, Dolly Parton, Frank Sinatra and Tom Jones, tailored to high-rollers.

In Aurora, there was talk of a new riverwalk, hotels, restaurants, condominiums. It seemed that the legislation had gotten it right. Joliet, too, had a popular riverboat; so did Elgin.

All of that is over now.

On a recent visit, the Hollywood Casino looked sad, diminished and a far cry from its glamour in the 1990s. Last month, its owner, Penn Entertainment, said it wanted to close the long-docked riverboat downtown and rebuild it on a site closer to I-88.

Penn Entertainment also announced a similar plan for the casino in Joliet, which it also owns. Better, it said, for the casinos to be near the expressway for easier access.

But what about the promises made to downtown Illinois? Suddenly, nobody seemed to remember that the whole justification for gambling in Illinois was downtown revitalization.

Illinois casinos, it seems, have become like NFL franchises, supremely skilled at lobbying and dangling the promise of revenue to cash-strapped cities but on their own ever-changing terms.

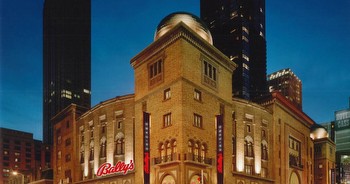

There’s a cautionary tale here. Casinos change the rules as they chase more money. Chicago has already seen a fascinating shift within its own new, long-awaited casino. The city initially announced it had selected Bally’s as the entity with which it was doing business and touted the likely rapid approval by the Illinois Gaming Board, due to Bally’s existing presence in the industry.

But in recent days, we’ve heard that not only is Bally’s selling the land for the casino and then leasing it back from Oak Street Real Estate Capital, but Oak Street Real Estate Capital will commit to provide up to $300 million more in additional funding to develop the casino. That begs the question of how involved Oak Street Real Estate Capital will be, and how the gaming board will feel about that.

Of course, the gaming industry has evolved since the 1990s. Most notably, sports betting has exploded and now casinos have found themselves subject to many of the same pressures as office buildings downtown. They have to persuade gamblers that they’re enough of a good time to get them to come to a central facility rather than merely getting their gambling fixes on their phone.

Entertainment has made a comeback, and casinos are now, in essence, selling a combination of convenience and a party atmosphere.

Millions of dollars have been made in Illinois in this industry over the past two decades, and politicians have not always been ahead of the curve.

We’ll just reiterate two abiding truths.

Outside of Las Vegas, at least, casinos are fickle entities that cannot revitalize cities on their own.

And they will promise the moon and then ask for the stars.