University of Iceland ‘addicted to slot machine income’

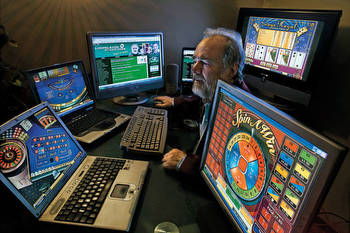

Iceland’s oldest university is facing mounting pressure over an unusual funding source in a country in which gambling is largely banned – Las Vegas-style betting machines.

The University of Iceland’s estates budget has been funded almost exclusively via a lottery since 1933, when the institution was granted an exemption from a nationwide prohibition, and the revenue stream is now worth about Ikr1 billion (£6 million) a year.

However, there is mounting concern about the impact of modern gambling machines with screens simulating spinning reels, which account for about one-10th of the lottery income. A 2017 study found that 67 per cent of problem gamblers in Iceland had used such machines in the previous year, making them the most popular way to gamble among those struggling with the habit.

“What we find in all our analysis is that [machines] are always significantly associated with problem gambling,” said Daníel Ólason, a professor of psychology at the University of Iceland.

The university’s slot machine take more than doubled between 2014 and 2019, after which pandemic restrictions caused many of the bars and pubs that host the machines to shutter.

That was welcomed by Alma Hafsteinsdóttir, chair of Iceland’s Association of Gambling Addicts (SÁS), who said the university understood the problems it has been causing.

“People are committing suicide, families are breaking up, and they know it, because people are calling the office asking for help,” she said.

Now there is mounting pressure for the machines to remain switched off for good, with a Gallup poll paid for by SÁS finding 86 per cent backing for this among Icelanders.

Within the university, Kristján Jónasson, a professor of mathematics, has collected about 300 signatures from colleagues who want the machines gone.

And Lenya Rún, a final-year law undergraduate who serves on the university’s council and is also a deputy MP for the Pirate Party, wants the institution to stop using the machines to finance itself. “The university isn’t going to go bankrupt if we don’t use the lottery machines,” she said.

Ms Rún, one of Iceland’s youngest parliamentarians ever, plans to open a debate on eliminating betting machines in the country’s legislature, the Althing, on 21 February. “If I can get support from some of the majority parties, I think that it could get through,” she told Times Higher Education.

The university lottery is run as a separate company, and Bryndís Hrafnkelsdóttir, its chief executive, said the firm was “very well aware of the risks that follow the [machines’] operation”.

However, she continued, the lottery had been proactive in promoting responsible play and had recently doubled its contribution to a state-supported addiction treatment body.

“The university lottery has really been the progressive guy here. Neither the government nor the other lotteries or anyone else has done anything about this,” said Eyvindur Gunnarsson, chair of the lottery’s board and a law professor at the university.

He said the university lottery had never advertised and had been trying to set up a digitised system introducing spending limits since 2017, but the efforts to pass regulation had been disrupted by changing governments.

Both lottery officials said that switching the lottery’s machines off for good would force users towards illegal, online alternatives.

“I’m sure that not only people fighting gambling addiction would like to see us go. I think also offshore competitors would be even happier,” Professor Gunnarsson said.

Aside from claims of inaction, Ms Hafsteinsdóttir said the university also had “no interest in researching the slot machines and the people playing them”, because this would reveal the severity of the issue.

Ms Hrafnkelsdóttir denied this and said the university had funded research into the prevalence of gambling problems in Iceland since 2004 and continued to do so.

Ögmundur Jónasson, who as Iceland’s interior minister between 2010 and 2013 tried to introduce centralised controls such as spending limits, said few minded the monthly ticket lotteries that bring in the bulk of the university’s gambling income.

But the “plague” of one-armed bandits that invaded the Nordic island in the 1990s were a “fundamental change” and the machines were “not moral”, he said.

“We are not criticising the lottery tickets the university has – that is very harmless. I have not yet met anyone who has lost all his or her [money] buying lottery tickets,” said Ms Hafsteinsdóttir.

“There are two kinds of addict: those who spend their money in machines, and secondly those who receive that money and benefit from it,” said Mr Jónasson.

“My eyes are on the authorities that condone this, the government and parliament. They have decided the university should be financed this way.”