The 'invisible addiction' of gambling has become more dangerous than ever in recent years. Here's how to avoid it

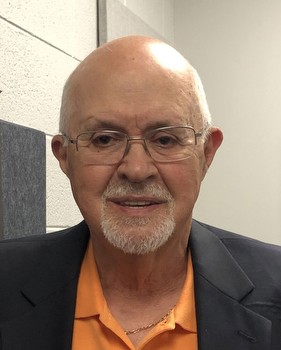

Noah Vineberg, a bus driver based in Ottawa, lost over $1 million to his gambling addiction.

Vineberg can trace the roots of his addiction all the way back to grade school, where he avidly traded marbles and hockey cards on the schoolyard.

“It wasn’t until much later — like 16 to 18, 19 — I knew that I was gambling heavier than anybody else. And I knew that I definitely had a problem.”

After 48 years of grappling with that problem, Vineberg will soon celebrate four years free from gambling.

But many others are still struggling. A University of Lethbridge study found that over 66 per cent of Canadians participated in some form of gambling in 2018, with 2.7 per cent identified as at-risk gamblers and 0.6 per cent identified as problem gamblers.

And while not all those problems are financial, they often come with a hefty price tag.

Online gambling has soared over the pandemic

Gambling has long been one of Canadians’ favourite pastimes. At more than $15 billion, it represents the largest section of the country’s entertainment industry, according to the Canadian Gaming Association.

And access to it has only gotten easier since April, when iGaming was launched in Ontario — making Ontario the first province to regulate internet gambling.

Ads and apps have been popping up everywhere since, even some featuring celebrities like Wayne Gretzky and Shaquille O’Neal.

Don’t Miss

But those ads can have a troubling effect, says Vineberg. Because while they may show people winning, “winners” are not who the advertisers are really trying to target.

“The client they’re after is the ‘me’ that’s going to go to four different cheque-cashing places … and going to just try and make enough on the weekend in my bets to cover my butt by Monday.”

And it’s only going to get more difficult for people like Vineberg.

Gambling as entertainment

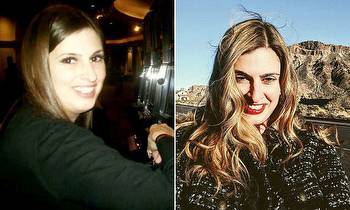

“The incidence of online gambling, and the severity of it, have increased considerably,” says Diana Gabriele, a gambling counsellor at Hôtel-Dieu Grace Healthcare (HDGH) in Windsor, Ont.

Gabriele adds the increased isolation during COVID-19 lockdowns hasn’t helped.

“As a result of that isolation, and the change in lifestyles and loss of employment, people became bored, they became strapped for money, they were looking for ways to make money easily,” she says.

“They were looking for entertainment.”

And entertainment they found. Gabriele explains that the rise of technology and “gamification” — the integration of video games into gambling platforms and vice versa — also increases the likelihood of people becoming addicted. It feels more rewarding when players can meet missions or tasks, earn loyalty points and bonuses or score highly in tournaments and leaderboards — and it keeps users engaged for longer, increasing their odds of losing more.

Mike Bergeron, a certified credit counsellor at Credit Canada, agrees.

“It’s just so easily accessible,” says Bergeron. “Everywhere you’re at — it’s on your phone, it’s at home on your computer, you can do it at work on your lunch break.”

What are some of the warning signs of a gambling addiction?

Gabriele says that the problem with gambling addictions is the issue is often not well understood.

“In the industry, we say that gambling is the invisible addiction,” explains Gabriele. There aren’t any visible effects of a gambling addiction, compared with drugs or alcohol, but there are still some major red flags you can look out for.

Spending more money than you initially intended to or pulling money from other sources to fund your habit is the No. 1 indicator, she says. Another concerning sign is if your habit starts to impact other aspects of your life, like jeopardizing your significant relationships, career opportunities or education.

Those are both signs Vineberg saw in his own life. At one point, he was siphoning off a percentage of his paycheque and keeping it in a separate account to hide his gambling from his wife. He also opened up secret credit cards and lines of credit to finance his habit.

“I owed money to everybody … I was stealing from Peter to pay Paul,” says Vineberg.

Set yourself reasonable limits

Setting firm limits on how much and how often you gamble can help you avoid sliding into risky behaviours. The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction recommends that you bet no more than one per cent of your household income before tax per month, and to restrict yourself to gambling no more than four days a month.

Ontario’s regulated gambling platforms include time and money limits. However, Gabriele notes that when a gambler’s behaviour becomes problematic, they may choose to reset these limits or turn to offshore accounts.

How you respond physically and emotionally to those limits can be telling as well. Gabriele says if you get irritable when you try to cut back or become overly preoccupied with gambling, that may indicate you have an issue.

“Even when they’re not gambling, they’re thinking about gambling, they’re planning on gambling, they’re trying to figure out how they can get more money so they can go back and gamble,” says Gabriele.

“Or they’re worried about not having any money at all, because they’ve spent it all on gambling,” she adds. “And of course, they’ll gamble even more, because that causes a great deal of distressed feelings.”

The first step to recovery is acknowledging the issue

An addict may soon find their problem has gotten so big that they can’t cover basic expenses, like their mortgage or rent payments.

“We’ve seen people go from six-figure incomes and very lucrative, satisfying jobs to living on the streets because of gambling,” notes Gabriele. “The journey can happen almost from the start for some people, and for other people, it can take many, many years before that becomes a consequence.”

Bergeron says the first step to getting out of this cycle is to acknowledge the issue and ensure you have systems in place to prevent you from going back.

“Even though there are solutions that could assist them in their debt or credit crisis, if we don’t adjust and do something about the behaviour that caused it, they will only become a Band-Aid,” says Bergeron.

How can you get your finances under control?

The second step is to look at your finances. Depending on the severity of your debt, you may want to consider everything from debt consolidation or refinancing your mortgage, to filing a consumer proposal or declaring bankruptcy.

“And then we start going through their income and expenses and trying to create a good action plan to live within their means, either to maintain their debt or to get out of debt at some point in the near future,” says Bergeron.

For some in the early days of recovery, it might be easier to take some of the decision-making out of their hands and limit their access to money by naming a financial trustee.

“Because one of the insidious factors of gambling is the lack of respect that one has for money — it gets converted into pretty little coins, you know, just numbers on a screen. It loses its importance to that person, it becomes depersonalized for them,” explains Gabriele. “And over time, they need to regain that respect and appreciation for money as a tool to provide safety and security in their lives.”

The sooner you seek help, the better

Vineberg made several attempts to get help for 15 years before he was ultimately successful. After three relapses — the last triggered by the event of his father’s death — he came clean to his wife at a therapy session, calling it his “first real accountability move.”

From there, he attended gambling counselling at the HGDH centre in Windsor. In the first year-and-a-half of his recovery, he had to consolidate a lot of his debts and hand the financial reins over to his wife.

“If there’s one thing that’s different in my recovery now than the other attempts, it’s that I am still actively participating, acknowledging, being accountable to and owning my recovery,” says Vineberg.

For anyone else who may be wrestling with the same, he emphasizes that the sooner you seek help, the better.

He admits the early days were hard. Vineberg and his wife lived on a fairly restrictive budget for a while and made sacrifices to get back on track. But because he sought out help when he did, the couple were able to take a two-week vacation to Italy earlier this year.

And he hopes that in bringing his experience with addiction to light, it’ll help others who may be struggling in the shadows.

“My son’s going to be 27 — my oldest — and I don’t tell him not to gamble,” says Vineberg. “I tell him … that if you start to notice that you can’t go without it, don’t be afraid to reach out for some help.”

This article provides information only and should not be construed as advice. It is provided without warranty of any kind.

.jpg)