Pa. lawmaker worked with casino lobbyists to author gambling bill

Emails to and from the legislature are normally shielded from public scrutiny, as lawmakers exempted themselves from having to reveal electronic communications when they revamped the state’s public records law in the 2000s.

Emails between Tomlinson’s office and Parx Casino’s lobbyists were unearthed as part of a little-publicized federal lawsuit by Georgia-based Pace-O-Matic, which develops skill games, against Stewart and his law firm, Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott.

The lawsuit revolves around accusations that Stewart and Eckert engaged in the legal equivalent of double-dipping by representing Pace-O-Matic while also acting as a lawyer for a competing interest: Parx Casino. Eckert, in court papers, initially denied the allegations, but earlier this year stipulated that the firm had not obtained “informed consent” from Pace-O-Matic when it decided to represent Parx.

In Pennsylvania, 1,150 registered lobbyists representing a wide array of businesses and industries court lawmakers in the hopes of influencing public policy. The very nature of their job requires them to research and analyze legislation, monitor bills, regularly attend legislative and regulatory hearings, and remain in frequent contact with people in positions of power.

The lobbying industry describes itself as a “legitimate and necessary part of our democratic political process,” according to the National Institute for Lobbying & Ethics, which represents lobbyists and government affairs professionals and promotes professionalism and ethical standards in the industry.

But good-government experts say having partisan interests writing bill language — which has become increasingly common in statehouses nationwide — harms public confidence in government.

“This can create a potential tension,” said Pete Quist, deputy research director at OpenSecrets, a nonprofit research and government transparency group that tracks money in politics and its impact on elections and policy.

“Elected officials should be representing what they view as the public interest, whereas the lobbyist is representing the interest of the client, and the public must rely on the legislator to recognize when that difference is or is not contradictory.”

‘The game plan’

In Pennsylvania, lobbying around gambling has been fierce since the state legalized slot machines in 2004. Since then, lawmakers have vastly expanded the types of games people can pay to play — including table games, online gaming, fantasy sports, and sports betting — and where they can play them.

One remaining sore spot? Skill games.

Critics argue skill games are not authorized by the state’s gambling law. Because they are not regulated by the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board, skill games are not taxed like other gambling devices. The state’s 16 casinos and mini-casinos, by comparison, pay a steep, 54% tax on revenues from slot machines.

Manufacturers like Pace-O-Matic counter that skill games aren’t casino gambling, as they rely on a level of cognitive and physical player ability, rather than on pure chance, to get a successful outcome.

They also note their machines financially benefit the establishments that house them, including many small, family-run businesses that get a cut of the revenue. Pace-O-Matic, for instance, said they provide store owners with a 40% cut of the revenue from their machines. State officials estimate there are over 50,000 machines across the state.

Casino owners want legislation banning skill games, and argue that legalization would further cannibalize the state’s already over-saturated gambling landscape. Skill games operators and distributors would prefer laws to tax and regulate their industry — although they have benefited financially from legislative stasis over how to best confront the issue.

Both sides have hired top lobbyists and lawyers, and have landed allies in the legislature who have introduced competing bills in recent years.

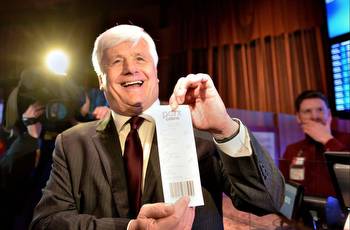

Tomlinson, a veteran lawmaker who played a pivotal role in ushering in the 2004 gambling law, is one of the most vocal advocates for banning skill games. He’s found a sympathetic ear in the State Police — which has seized some of the machines, leading to prolonged litigation — and the State Lottery, which contends the games eat into its revenue.

Though casinos, like most businesses, took a direct financial hit when they shut down during the pandemic, they have made an eye-popping comeback. Last year, in fact, was a record year for gambling revenue, with the industry pulling in just over $4.7 billion.

Even within that windfall, Parx distinguished itself as the top-earning casino in Pennsylvania. It topped the charts last year in revenue from slot machines ($409 million) and table games ($207 million), and was among the top five for revenue from iGaming and sports wagering, according to the state Gaming Control Board.

Though casinos were banned from making campaign donations for the first 15 years of legalized gambling in Pennsylvania, a federal court ruling in late 2018 removed that barrier. Since that time, Parx’s chairman, Robert W. Green, has contributed $323,500 from his political action committee, the 2999 Group, to various candidates across the state, according to campaign finance reports.

Tomlinson, records show, has received $10,000 from that PAC since 2020, when it was first launched.

Skill games operators and manufacturers also contributed big money during that same time frame to state lawmakers and other elected officials — just under $680,000. Last summer, however, several high-ranking senators, including the top Democrat and Republican in the chamber, returned donations they had received from the skill game industry, citing the fact that it was still unregulated.

Parx’s lobbyists and executives appeared to take some credit for the reversal. “When the parade changes direction, run around to the front of it,” Parx’s chief operating officer wrote in a June 2021 email.

Dick Gmerek, a top Harrisburg lobbyist representing Parx, responded, “We all pushed the parade in That direction…..with Rommy’s help obviously.” Gmerek did not respond to requests for comment about his emails, including clarifying whether “Rommy” referred to Tomlinson.

In 2019, when Tomlinson introduced his bill, the new, two-year legislative session had just started, and the fight over skill games was being waged in both the Capitol and the courts. In early April of that year, emails show, lobbyists for Parx met with Tomlinson and Skoczylas, his chief of staff, to strategize about Tomlinson’s bill.

“The game plan Tommy laid out is as follows,” Gmerek wrote in an April 9 email to Stewart, Sean Schafer, and two Parx executives, including Green. (Schafer is another Parx lobbyist and a former Tomlinson aide.)

The plan, according to Gmerek’s email, included Tomlinson calling a meeting of casino lobbyists to divvy up calls to senators to take their pulse on the issue and report back to Tomlinson. That meeting, subsequent emails show, was scheduled for mid-April in Tomlinson’s office.

A few days after that meeting, Skoczylas emailed Gmerek, Schafer, and Stewart seeking draft language for a bill banning skill games. Stewart followed up within hours with a proposal, and again on April 30 with a revised version.

On May 15, Skoczylas sent the lobbyists the most up-to-date version of the bill, which included a few edits from Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s office: “Got this back from the Govs office. Let us know what you think.”

Another staffer from Tomlinson’s office a week later emailed the lobbyists with the proposal’s final language, asking for input.

The bill that Tomlinson introduced at the end of the month contained near-identical language to the draft that Parx’s lobbyists had drawn up.

.jpg)