Las Vegas Sands looking at Long Island sites for casino

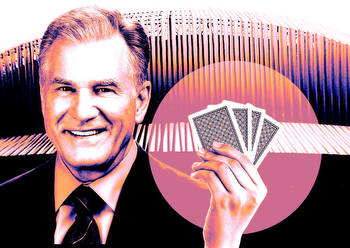

One of the world’s largest gambling businesses, Las Vegas Sands Corp., is looking to build a casino on Long Island at the suggestion of its senior vice president David A. Paterson, a former New York governor.

“We don’t know where the location is at this point,” Paterson said in a Newsday interview on Thursday. “But I’m the one who suggested that they look at Long Island because of all the congestion in Manhattan.”

The Nassau Hub, including Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum, is one of several sites that Sands is considering, according to sources who requested anonymity.

Paterson and other Sands executives spoke to members of local chambers of commerce on Thursday about the company’s plan to win one of three state licenses to operate a casino downstate.

The state gaming commission will open the application window next month. However, no licenses are expected to be issued before late 2023, officials have said.

Paterson predicted the owners of Resorts World New York City at Aqueduct raceway in Queens and Empire City Casino at Yonkers Raceway in Westchester County — both consisting of electronic gambling choices — will win licenses to convert to full-scale gaming.

So, Sands is hoping to secure the final license, he told about 100 people who attended the joint meeting of the Nassau Council of Chambers of Commerce and the Suffolk County Alliance of Chambers. The two-hour event was held at the South Farmingdale Fire Department building.

Long Island’s proximity to LaGuardia and Kennedy Airports make it an attractive casino site, according to Paterson, who lives in Harlem but attended grade school and law school in the Town of Hempstead.

“The most important thing about the location of a casino is proximity to the airports because a very high percentage of gamblers fly around the world and go to these casinos,” he told Newsday, referring to high rollers. “So, Long Island, particularly right at the edge [with Queens], you can get to the airport in 15 minutes sometimes.”

Paterson also said Queens, particularly land adjacent to Citi Field, and Coney Island in Brooklyn have been mentioned as possible casino sites by developers.

But Manhattan is a poor choice, asserted Paterson, downplaying potential projects from Sands' competitors.

"I don't know why people are thinking about putting a gaming facility in [Manhattan's] central business district, between 34th Street and 59th Street, given all the challenges that COVID-19 brought us and trying to get people back in office buildings," he said. "And now, we're going to charge [motorists] $25 to come in the area" as part of a congestion pricing plan to help fund the MTA. "In my opinion, gaming just is not functional in Manhattan."

At the chambers' meeting, Sands executives Ron Reese and Norbert Riezler said it typically invests between $3 billion and $4 billion to construct a casino, though only about 10% of the floor space has slot machines, card tables and other gaming. They said more than 50% of patrons never place a bet, preferring to see a show, have a meal, use the spa or have drinks with friends.

Reese, responding to questions from Ryan Stanton, executive director of the union umbrella group Long Island Federation of Labor, pledged that Sands would use union construction workers to build a casino in downstate and not fight efforts to have its employees join unions.

John Callahan, former mayor of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, said a Sands casino on the site of a shuttered steel mill has revived his community, providing much-needed supply orders for small businesses and lodgers for hotels. More than 10 million people visit the Wind Creek Bethlehem casino each year, he said.

Kristen Reynolds, CEO of the tourism promotion agency Discover Long Island, said a casino complex with large meeting rooms would allow for big conventions to be held here.

"I've had to turn away $35 million in conventions in the last few years," said Reynolds, who once worked at a Native American-owned casino in Arizona.