‘I lost £5 million because of my gambling addiction’

A father who became suicidal after gambling away more than £5 million has told how his life was destroyed by addiction.

Mark Bradshaw said his life “spiralled and crashed” after he became secretly addicted to gambling in a two-decade ordeal that cost him his job, his relationship and almost his life.

The 40-year-old spoke out as the government announced long-awaited plans to force companies to step up checks on punters as part of efforts to address problem gambling and guard those most at risk of harm.

The much-delayed white paper includes rules to lower maximum bets, require more background checks, and a new levy to fund research and treatment for problem gambling in a series of measures designed to target the online industry.

‘Gambling companies were no different from a drug dealer’

Mr Bradshaw’s addiction began when he visited a casino with a group from his rugby club, aged 18. He became “fixated” with roulette and blackjack and quickly became a repeat customer.

As his gambling habit developed, his rugby career and subsequent military career came to an end. At age 23, he missed a military commitment so he could place bets at the races. While there, he ended up in a fight and was arrested. He says he was later acquitted, but was fired from the military.

Things got even worse for Mr Bradshaw when he moved into a job in recruitment and was suddenly taking home much larger pay cheques.

“I was incredibly good at my job, so I was making tens of thousands of pounds a month and became a millionaire virtually overnight - but with no guidance or control,” he told The Independent.

He recalls betting £50,000 on the day of the Jubilee in 2012. “I lost it all. That should’ve been a really good day for my kids, but all I was bothered about was being on my phone and thinking ‘jeez, I’ve just blown £50,000’.”

Mr Bradshaw’s work started to suffer as he became obsessed with making money just so he could gamble it away.

“Things started to crash down and my debts increased,” he said. “Winning would make me jubilant and then I’d keep upping my bets and end up in more of a hole. I started thinking that if I could win then it would all be solved, so I thought the way to get out was to gamble more.”

Mr Bradshaw’s wife and two sons did not know for a long time that he was a gambler. Three-quarters of those experiencing problems with gambling feel they cannot talk to loved ones about it, with stigma being the biggest barrier preventing people from opening up, according to new data by the charity GambleAware.

He described being in the throes of addiction as “exhausting and anxiety-ridden”. He was constantly “rationalising and normalising” his levels of gambling until he had spent millions.

When his family found out what was going on, “everything spiralled and crashed”. “My wife said she wanted me out and didn’t want me there,” he said. “I realised I needed to sort my life out.”

Mr Bradshaw boarded a boat to Portugal. “I suddenly thought ‘I don’t have anybody, I’ve burned every relationship I had’.” This was when he thought about taking his own life. But, he added: “I couldn’t die being a gambling junky who took everything from my sons.”

After more than 20 years, Mr Bradshaw, who is originally from Yorkshire but now lives in Dublin, has kicked his gambling habit and says he is in a stronger place than ever. He has a new partner, with whom he had a daughter in 2019, and has taken up extreme sports to give him some of the adrenaline rush that gambling used to give him.

Although he takes full responsibility for his actions, he believes there were not enough barriers in place as he battled addiction. “Gambling companies were no different from a drug dealer, pushing me to bet,” he said.

‘It destroyed my entire life’

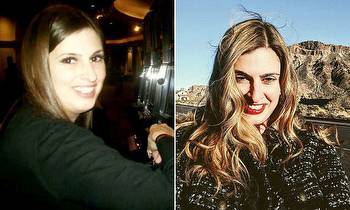

Stacey Goodwin, 30, from Derbyshire, knew nothing about the gambling industry until she got a job in a betting shop. She placed her first £1 bet aged 18 and ended up winning £36. It left her wanting more.

“That money was enough for a night out,” the now 30-year-old said. “It felt amazing, a real buzz. It was so fast, so simple, so colourful - and there were bonus rounds you were constantly chasing. I was drawn in by those bright lights, I was hynotised.”

What began as a desire to make a bit of extra money for a night out soon became a need to make back money she was losing - as well as a chance to chase that “buzz”.

“I started hiding it,” she said. “I was aware an 18-year-old girl gambling is not something you’d normally see. I would move between betting shops. I was ashamed of myself.”

Online gambling posed the solution. “I was on the toilet at midnight every payday waiting for the money to come in,” she said. “Then I’d stay up for the next six hours until it was all gone.”

She said she lost hundreds of thousands of pounds over the eight years of her addiction, spending “every single penny” that went through her hands. It got to the point when she couldn’t even afford a tin of soup so she wouldn’t eat.

By “lying and manipulating to feed this urge to gamble”, she said she destroyed her relationships, which included gambling away her partner’s mortgage payments.

She was left isolated and “incredibly depressed”. “I weighed less during my gambling addiction than I did during the eating disorder I’d had years before,” she said.

“It destroyed my entire life. I made two attempts to take my own life - it was absolutely horrific. I felt hopeless and genuinely believed the only way out was to end my life.”

At one point, Ms Goodwin won a jackpot of £50,000 but felt nothing except sadnes. She gambled it all away. “I realised it didn’t matter how much I won - it would never be enough,” she said.

Ms Goodwin checked herself into a women-only retreat facility. Sitting talking to two women there, she said: “For the first time in my life I felt hope that maybe I could change.”

Despite one relapse, she is now more than three years into her recovery and has begun her own support group, Woman.Empowered, to help support women who have been in the same situation. “I’m trying to remove the shame and stigma, which is absolutely more [acute] when it comes to women,” she said.

Directly addressing those battling gambling addiction, she said: “You’re not on your own and it’s not your fault - no one ever places a bet to become addicted to gambling.”

You can visit the NHS website for help with gambling problems.

Samaritans can be contacted on their free helpline anytime on 116 123.