Gambling with our youth

March Madness came to an end on Monday night, when the Connecticut Huskies defeated Purdue to win their second straight NCAA men’s national basketball championship.

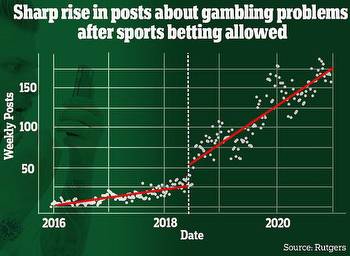

But the biggest losers were the students who gambled away money on the game. And the real madness is that we allow sports-betting companies to flood the zone with advertising, which lures millions of young people into placing wagers with a single click on their phones.

According to an NCAA survey conducted last year of Americans aged 18-22 — mostly college students — 58% have engaged in sports betting. Among those who live on a college campus, 67% report doing so.

Sixty-three percent of on-campus students recall seeing gambling advertisements — a higher fraction than the overall American population — and 58% said they were more likely to place a bet after seeing an ad. Clearly, the gambling industry is wagering on college students.

And it’s paying off. In the NCAA survey, 4% of respondents reported betting every day, and 6% said they had lost more than $500 in a single day. People with college degrees are less likely than others to engage in most forms of gambling. But in sports betting, the biggest increases have been among young, college-educated men.

Advertising isn’t the only reason for that burst, of course, but it surely makes a difference. The sports betting industry spends about $2 billion a year on it. A survey last year showed the public overwhelmingly dislikes the betting ads, but they wouldn’t exist unless they worked.

And we have good reason to believe they work especially well on younger customers, who have less impulse control anyway. Most seasoned gamblers know that a parlay — which combines the odds of multiple wagers into a single one, with a larger payout — is a sucker’s bet. But it’s hard for a novice to resist a parlay if they see Charles Barkley or Jamie Foxx touting it on TV.

That’s why U.S Rep. Paul Tonko (D., N.Y.) introduced a bill last year to ban sports-gambling advertising, which he likened to advertising for cigarettes. “This is a public health crisis,” Tonko said. “They’ve replaced Joe Camel with celebrity spokespeople.”

Remember Joe Camel? He was part of a century-long effort by the tobacco industry to hook young people on cigarettes. And that worked, too.

“School days are here,” an R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company official told sales managers in 1927. “And that means BIG TOBACCO BUSINESS for someone. Let’s get it — and start after it RIGHT NOW.”

It was illegal to sell cigarettes to minors, just as most states ban sports betting until you’re 21. But that didn’t stop the cigarette companies from seeking underage customers. In 1973, one Reynolds researcher suggested searching high school history textbooks to find people and images that teens would recognize, which could then be adopted as brand names. And at Lorillard, which manufactured the popular Newport brand, one official privately admitted that “the base of our business is the high school student.”

The industry also used cartoons like Joe Camel, which helped the Camel brand raise its share of the under-18 cigarette market from less than 1% in 1987 — when the cartoon was introduced — to 33% just three years later.

By 1991, 90% of 6-year-olds — and nearly 100% of teenagers — could recognize Joe Camel. Only in 1998 did cigarette companies agree to stop advertising with cartoons, as part of a lawsuit settlement. They can’t use celebrities in their advertisements. And, of course, cigarette ads have been banned from television for over a half-century.

By contrast, sports-gambling ads saturate our airwaves. “I haven’t seen an online sports betting ad in almost seven minutes,” comedian Conan O’Brien tweeted in 2022. “Am I dead?”

And if you think the ads aren’t targeting young people, think again. Indeed, gambling companies have partnered with colleges — yes, you read that right — to get more students to bet. After Louisiana State University struck a deal with the gambling giant Caesars, the school sent an email urging students — including some who weren’t old enough to gamble legally — to “place your first bet (and earn your first bonus).” The University of Colorado entered an agreement with PointsBet, which gave the school an extra $30 for every new student who signed up with the university’s promo code and placed a wager.

Amid a flood of negative publicity, both institutions . But all of us have made a devil’s bargain with the sports gambling industry by letting it advertise in whatever ways it wants. We might start by copying Ontario, which recently barred gambling companies from featuring celebrities in their ads. If Joe Camel can’t push cigarettes, why is Jamie Foxx allowed to promote sports betting?

It’s not enough to urge viewers to “gamble responsibly,” or to provide a hotline for people who don’t. Unchecked advertising is gambling with the well-being of our young people. And that’s a bet we can’t afford to lose.