Gambling killed my husband. We must stop this predatory industry claiming more lives

This time last year, my husband Luke and I had everything we wanted: each other, a lovely house and two wonderful children. Three months later, this life was shattered. On 22 April 2021, my wonderful partner took his own life.

About two years before his death, Luke developed a gambling disorder. He started gambling with friends on a Saturday, placing bets at a local bookies while watching Leicester City, his football team. At the time, I didn’t think it was dangerous – I had no idea that gambling kills so many people.

Soon, Luke began to bet online. He opened multiple accounts, taking advantage of “free bets” – aggressive marketing offers used by online bookmakers to lure people into gambling. From there, he was encouraged to bet on sports, like horse racing, that he knew little about. It didn’t take long for him to get into a lot of debt and start chasing his losses.

If you knew Luke, you’d find it hard to comprehend that he gambled. My husband was sensible and careful with money. He would save whenever he could, and bills were always paid on time. As a warehouse manager at a local family printing firm, he often found ways of saving the company money, something he was held in high regard for.

I only became aware he was in trouble after I noticed he was struggling to pay for cinema trips or meals out. Gambling on a phone is very isolated, and it took me a year to understand he was gambling so much. We had just sold our house, so luckily we could pay off the debts he had accumulated and, much to my relief, Luke closed his gambling accounts. This seemed enough. Luke had never had issues with gambling before and I had no reason to think he would again.

But in 2020, Luke was furloughed because of the pandemic. He began gambling again in secret, reopening his old accounts. I remember him often commenting on how relentless the marketing emails he was getting were; he was concerned about the impact they would have on people who were already struggling with money. Naively, I thought this meant Luke could stop gambling when he wanted to – like the GambleAware slogan: “When the fun stops, stop.”

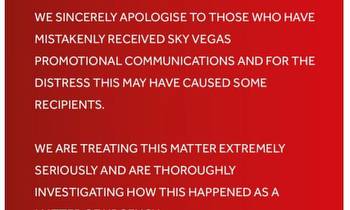

Three weeks after his suicide, the police gave Luke’s phone back to me. It was then that I realised his gambling disorder had returned. His relapse was so rapid that I still cannot believe it was never picked up by these gambling companies who – at the start of the pandemic – had promised to do more to protect vulnerable customers like Luke. On one account he reopened during the pandemic, the pattern of his gambling was obviously harmful. He took advantage of a free bet offer, deposited money, lost money, was immediately advertised another free bet offer, and the cycle would begin again.

It is not in the gambling industry’s interests to stop people developing gambling addictions. It spends £1.5bn a year on advertising to bring in customers to get hooked on its products for profit. Some 60% of its profits come from from 5% of customers who are already problem gamblers, or are at risk of becoming so. And they are huge profits – the UK industry is worth about £14bn. These companies know a staggering amount about their customers – in some cases they will know if someone earning £30k a year has gambled £60k in a few months, and do nothing to stop it. They track their habits and patterns and vulnerabilities online to find out when best to advertise to them and what kind of emails they are most likely to open. They could, if they wanted to, use this information to help people, to block their accounts; but often they use it to drag them further into addiction. When people like my husband try not to gamble, they are targeted more aggressively. One gambler who got his data back from an online gambling company and shared it with the New York Times found that as someone who had given up gambling, he had been profiled as a customer to “win back”.

How do these gambling companies get away with it? Because they can. The entire industry is fuelled by a money above all else mentality that is devoid of morality.

In a 2021 report, Public Health England estimated that there are more than 409 gambling-related suicides in England every year. That is more than one life lost every single day. That is why I am campaigning for “Luke’s law” – to ban gambling incentives such as “free bets”. Luke found that being bombarded with ads from that 24-hour bookies and casino in his pocket made it a problem that became impossible to escape. Banning these incentives may go some way to alleviating the misery that gambling companies cause families like ours with their predatory actions.

The gambling lobby is very powerful – just look at all the MPs who get paid off with tickets to sports games to speak in its favour. But unlike so many who caution against change to gambling regulation, I am not on anyone’s payroll. I would give anything for this catastrophe to not have happened to me and my family. It has been traumatic and the fight is draining, but I do not feel I have a choice. The government is currently reviewing gambling legislation – laws that were drawn up before smartphones. This is a real chance to make changes that could benefit everyone – not just the few who are making money from misery.

We banned tobacco marketing; we can do the same for gambling.

My children will never see their father again. But I hope that by getting Luke’s law passed, he may have saved others from falling for the same fate. It gives me some small solace, and I hope it gives our children that too among their grief.

Annie Ashton campaigns to raise awareness of gambling addiction